Social Media - Challenges for Lawyers and the Courts

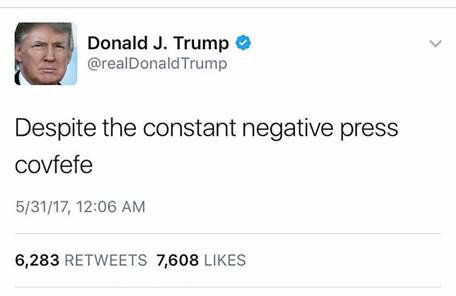

Australian Young Lawyers' Conference

1. As the clock ticked into the early minutes of morning on Wednesday, 31 May 2017, all was quiet on the streets of Washington DC. The journalists and political operatives that track the Twittersphere were ready to switch their phones to silent and get some much-needed shuteye for the day ahead. Until … ding! At 12.06am, the 45th President of the United States of America, Donald J Trump, had something to share with his 31 million followers about the state of the union. The President is never one to hide his light under a bushel, especially when discussing his concept of fake news. The Twitter post began: "Despite the constant negative press covfefe".

2. And then … nothing. Minutes passed. The Twitter faithful and not so faithful blinked at their screens in confusion. The tweet was not deleted. By 1am the tweet had consumed the Twittersphere, rising quickly to the top of the list of trending topics. No one at the White House could be reached for comment. The jokes began to come through thick and fast – was this a shout-out to former FBI director James "Covfefe", or was the teetotal President merely placing his morning Starbucks order for a large "covfefe"? One reporter at NPR resorted to the Merriam-Webster dictionary for answers, tweeting: "Help, @MerriamWebster"[1].

3. The suspense continued throughout the wee hours of morning, until just after 6am, when the Commander-in-Tweet finally resurfaced. He deleted the tweet and posted another: "Who can figure out the true meaning of 'covfefe'???" POTUS wrote. "Enjoy!"[2] Obviously, this is a new social media version of the 19th Century parlour game of charades. Little about "covfefe" became clearer in the days and weeks to come. The White House press secretary at the time, Sean Spicer, revealed, "The President and a small group of people know exactly what he meant" but did not elaborate further. Hillary Clinton revealed her thoughts to a crowd in California: "I thought it was a hidden message to the Russians"[3]. Perhaps we will see a new entry in the next update of the Oxford Dictionary between "covey" and "covid".

4. President Trump's tweet is a good example of an unintended consequence of the use of social media. Early morning typos can be just the tip of the iceberg. As young people who have grown up with the advent of social media, as opposed to those seeking to age gracefully in avoiding it, many in this audience will be familiar with the challenges it can pose: I have been told, on good authority, that it can be a challenge to squeeze one's witty thought or opinion into a mere 140, or, soon to be 280, characters on Twitter; to choose which Instagram filter best captures the deliciousness of one's Sunday brunch order; to attempt furiously to delete an embarrassing comment left by one's aunt on a Facebook post; or merely to keep up with the latest social media app that appears to have taken the world by storm. However, luckily I have not had to face these overwhelming problems. But I wonder if it is possible to imagine a legal world where the parties' pleadings and submissions could be limited to 140 characters.

5. The rise of social media presents a myriad of challenges for professional practice as young or older lawyers. The complexity and constant evolution of social media also poses its own unique difficulties for the Courts and judges too. Despite the possible vast range of issues that I could traverse, I intend to focus principally on two. First, whether and, if so, how the courts, judges and lawyers should engage with or on social media. Secondly, how public use of social media to attack judicial officers and courts can have impacts on the administration of justice and what steps the legal system can take to address this.

What is social media?

6. Social media, like the platforms from which it is delivered, appears to be ever-evolving and becoming more complex. It is a phenomenon that, in many ways, is difficult to define. Most simply, it refers to a kind of social interaction via technological means[4]. Nonetheless, social media communication is often capable of being categorised as a monologue rather than a dialogue or a true interaction. Presidential tweets are one-way outpourings of what may just have popped into the Tweeter's mind. They may be calculated to produce a reaction but it is a reaction that does not involve the person who tweeted having to deal directly with any one or all of his 31 million followers.

7. Popular social media platforms include Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Whatsapp, Snapchat, YouTube and LinkedIn. Through these platforms, any user, whether an individual, a corporation or an organ of government, can share information, connect with other users, and comment on or react to others' posts. The numbers of users across the globe are staggering. In April 2017, there were reportedly 1.55 billion Facebook users, 1 billion YouTube users, and 320 million Twitter users[5]. While some people have been resistant to the tide of social media, no one in modern society can avoid the phenomenon completely. The question for today is how and can the judiciary and legal profession deal with it?

8. A particular feature of social media is the scope of publication it affords to users. In perhaps, what is becoming, a bygone age, the owners or journalists of mass media, that is the publishers of newspapers, radio or television broadcasters, could be sued and held accountable for defamation or be restrained from publishing matter either by injunction or because it was likely to interfere in the course of justice, such as by being prejudicial to a party, usually the accused, in court proceedings. But social media is a different beast to mass media. A publisher on social media can be anonymous. A 1993 cartoon in the New Yorker depicted two dogs at a computer screen, one with her paws on the keyboard saying, "On the internet, nobody knows you're a dog"[6].

9. And that is why the recent expression "fake news" is connected to the use of social media – its publisher, almost invariably, is anonymous and undiscoverable. He or she says whatever they want. In days past this could be seen as propaganda, but then one could identify its source and assess its authenticity or credibility accordingly. Not so on social media.

10. There is a power in the printed word, be it seen in a newspaper, in a book, on a computer or on a mobile device's screen. In addition, some social media has the capacity to extend the longevity of what were once transient broadcasts on radio or television. Now one can view a video on YouTube as often as one likes or replay a radio broadcast. It is one thing when these are a form of pure entertainment, but another when the subject of the piece is a human being or, as we are now seeing in politics, a public issue. The permanence of the form in which a message is delivered can add to its contemporaneous appearance of authority and authenticity.

11. It is no good today to discover that yesterday's news that ended a political career, an idea or a life, was "fake news". Mud sticks and experience affirms that, generally, what is done cannot be undone. Social media has been used as a means of bringing forceful, sometimes overwhelming, pressure to bear on an individual or a business or a political party against which it is directed. School children regularly report bullying on social media. Social media can be used, as well, as a means of creating a feeling of pressure on a person to conform to the position it advocates.

12. Yet, it is frequently the case that the anonymous instigator of a social media post or campaign has eschewed any responsibility for the consequence of his or her or its conduct. The instigator of a post can be anyone, anywhere in the world. Once unleashed the post often cannot be controlled by others, including courts, and the person who is responsible for the post cannot be found, sued or otherwise held accountable. These faceless men and women are often cowards hiding behind the shield of anonymity to wreak damage on others freely as they choose. The law in any one country is correspondingly powerless to control or provide a remedy for conduct that is unlawful, illegal or a breach of private law rights. In many ways, social media is beyond the reach of the law that is essential to the regulation and governance of all societies including ones like ours that are democratic and free.

How the courts, judges, and lawyers engage with social media

Australian courts

13. Australian courts have increasingly engaged with social media, whether that be by establishing social media accounts, allowing social media reports of court proceedings or receiving into evidence of social media publications in civil and criminal proceedings[7].

14. Today, at least 11 Australian courts and tribunals, including the Federal Circuit Court, Family Court and the Supreme Courts in New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, South Australia and Tasmania, have active social media accounts. These are generally used to publish judgments and court-related information[8], as well as to advise about court appointments, media reports and administrative matters[9]. Although the Federal Court of Australia uses the internet to provide access to a great deal of material, including judgments, the complete electronic court file for every case filed since October 2014, court lists and practice notes, that Court does not currently have any active social media accounts. The Court has indicated that it may consider using social media to engage the public in the future[10].

15. There are several perceived benefits for Australian courts in using social media. In April 2011, the Supreme Court of Victoria became the first court in Australia to set up a Twitter account, indeed this is possibly its first Tweet.

In August 2011, the recently retired Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Victoria, the Honourable Marilyn Warren AC, stated that the "courts should take advantage of social media such as Twitter and Facebook to better explain themselves to the public"[11]. That court and the Victorian Country Court provide access to live stream sentencing remarks in criminal cases. Making proceedings more accessible to the community through social media platforms will usually be consistent with promoting transparency and public confidence, and improving community engagement with the courts[12]. Of course, there have to be limits on this, including in cases involving Government or trade secrets and the welfare of children.

16. However, there are also some unique challenges that courts can face through social media engagement. If courts are seen as increasingly available to the public through social media, will persons expect that courts should respond to their comments or queries? As Judge Judith Gibson, of the District Court of New South Wales, has noted:

"How will the interactive nature of social media affect the discourse between the court and litigants? Will social media require courts to take court 'user' satisfaction into account in the provision of justice, and how is the dissemination of judgments on social media affecting public perceptions of traditional rules such as the doctrine of precedent?"[13]

17. Often it will be challenging and time consuming for a court to provide a sufficiently nuanced and accurate description of issues in a case within the constraints of social media[14]. Distilling a complex 100 page judgment into an 140 character tweet is likely to result in misstatement, oversimplification or "covfefe".

18. Further, were the public able to engage directly with the courts in the uncontrolled online world of social media there would be issues of how to ascertain whether a user was a vexatious litigant or a person seeking to damage the court's authority or reputation, as well as concerns about personal privacy and security. Some courts, like the Family Court of Australia, have chosen not to allow the public to post or comment in reply to matter appearing on its social media pages. This is a means to prevent the identification or harassment of children, parties or witnesses involved in family law proceedings[15]. Moreover, s 121 of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) creates an offence in certain circumstances where a person publishes details about a case in a way that identifies a party.

19. Another challenge that the courts have had to grapple with is the use of social media in the courtroom itself. Should journalists or others be allowed to use their devices in the courtroom so that they can tweet updates of proceedings in real time? The use of social media in court proceedings is regulated in most Australian courts by legislation, rules of court, practice directions or policies. For example, in the Federal Court, unless the Court otherwise orders, rule 6.11 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) prohibits anyone from using any communication devices in the courtroom, including to access social media. Notably, however, the first case to be live-tweeted occurred in the Federal Court. In Roadshow Films Pty Ltd v iiNet Ltd, Cowdroy J chose not to prohibit two journalists in the courtroom from using Twitter. His Honour noted in his judgment summary[16]:

I understand this is the first Australian trial to be twittered or tweeted. I granted approval for this to occur in view of the public interest in the proceeding, and it seems rather fitting for a copyright trial involving the internet.

20. The Victorian Supreme Court has a policy permitting accredited journalists to use electronic devices in court, although any other persons must receive the permission of the presiding judge to immediately publish any material while in court[17]. By contrast, the use of social media in New South Wales courtrooms is forbidden[18], although there is an exception for journalists[19]. The High Court's ban on electronic devices in the courtroom led it to provide the media with a 'spill-over' room during the politicians' citizenship cases last week, where journalists could tweet and track the case to the Twittersphere.

21. As we know, updates or posts on social media or through the internet occur instantaneously. This increases the risk that journalists or others in a courtroom could use social media or the internet to publish or accidentally reveal material the subject of an existing, or subsequent, order suppressing the material that could amount to a contempt. The South Australian Supreme Court has addressed this issue. It permits "live" tweeting by bona fide members of the media, but with a 15 minute delay before a post so as to ensure that any application for a suppression order can be made[20].

22. Further, while juror misconduct is nothing new – an English jury in the 1990s consulted an Ouija board to arrive at their decision[21] – there are also instances of jurors using social media inappropriately in the courtroom. For example, look at this photograph that was posted on Instagram last year:

23. Now, the photograph above of a coffee cup may appear to be innocuous. However, its appearance in social media almost caused a Queensland murder trial to miscarry.

Source: Alexandra Blucher, 'Gable Tostee juror's Instagram posts a sign Jury Act must roll with the times, legal experts say', ABC News, 21 October 2016 <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-10-21/tostee-juror-instagram-posts-sign-jury-act-needs-review/7952550>

The person who made this Instagram post and others like it was a juror in the trial of Gable Tostee. The juror added captions discussing the difficulty of the case and its high-profile nature. On the fourth day of the jury's deliberations, counsel for the accused applied for a discharge of the jury, which was ultimately dismissed by the judge[22].

24. In 2015, a man who had been sitting in the public gallery during a rape trial in England sent a member of jury a "friend request" on Facebook. He was associated with the defendant. The judge ultimately discharged the jury because of the potential of that conduct to tamper with the jury. He continued the trial alone and convicted the defendant[23]. Likewise, in some high profile cases, judges have received unsolicited "friend" requests on Facebook from complete strangers or "randoms".

25. Such requests, on one level can be benign but on another can be threatening, especially as it suggests that the person making the request has had access to some information on the judge's Facebook page and possibly more, depending on how sophisticated the judge was in manipulating Facebook's privacy settings. On other occasions such "randoms" send the judge abuse on social media platform. Moreover, a person who has a Facebook page or other social media presence before appointment to judicial office may be unpleasantly surprised to learn that he or she cannot delete themselves or unsubscribe from Facebook – another evil of social media.

Australian judges

26. That brings me to the question, should judges use social media? Australian judicial officers do not have official social media accounts. However, they can choose to post, tweet, connect or, indeed, share a photo of their Sunday brunch or family occasion, in their private capacities. Often they will have social media accounts to connect with family and friends. The judicial role, like other traditional roles in our society, cannot stay static. Yet, in evolving to adapt to the new communication norms of our age, judges will need to develop careful insights and behaviours to protect not only themselves and their family's safety, but also the integrity of their office and the court.

27. When one becomes a judge, he or she accepts certain new responsibilities, ethical obligations and constraints on his or her behaviour. A judge's use of social media has the potential to impact significantly on the judge's place in society and society's perception of him, her and the courts as an institution. This has provoked the courts to provide guidelines on judges' use of social media. This month the Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration has sent to the Council of Chief Justices a draft third edition of the Guide to Judicial Conduct which includes two new chapters on the use of by judges and their families of social media and its potential to affect their lives. If the Chief Justices approve the updated contents of the Guide, it will soon be published.

28. In 2013, Chief Justice Allsop of the Federal Court issued 'Guidelines for Judges about using electronic social media'. He said that the guiding principle is[24]:

"A judge may use electronic social media, but in doing so he or she should have regard to the guiding principles of impartiality, judicial independence, and integrity and personal behaviour set out in the Council of Chief Justices' Guide to Judicial Conduct. Any conduct by a judge that would undermine these principles or create a perception of impropriety or bias should be avoided".

29. Similarly, the 2016 edition of the United Kingdom Guide to Judicial Conduct states that it "is a matter of personal choice" for judicial officers whether they use social media. But, it warns that judicial officers should not identify themselves as members of the judiciary on their or another's blog, and must avoid expressing opinions which could damage public confidence in their own impartiality or in the judiciary in general[25].

30. In particular, judges must consider how engaging with social media will not only affect, but may be perceived to affect, their judicial role. Should judges make connections publicly, or at all, through social media with members of the legal profession, including those who are close friends? Can such connections create possible issues of actual or perceived bias, require disclosure or lead to disqualification, especially if the person with whom the connection occurs is counsel or a partner or employee of a law firm acting in proceedings before the judge?

31. The Maryland Judicial Ethics Committee in 2012 noted a concern that being designated as a "friend" of a judge on a social networking site might be perceived as indicating both that the person is in a position to influence the judge, and may have ex parte communications with the judge using that medium[26].

32. In such a context, a judge with a social media connection to a participant in a case will have to consider whether the connection was one by reason of which "a fair-minded lay observer might reasonably apprehend that the judge might not bring an impartial and unprejudiced mind to the resolution of the question the judge is required to decide", in the words of Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ in Johnson v Johnson[27]. As their Honours noted, the test "is founded in the need for public confidence in the judiciary"[28].

33. Australian courts do not appear to have addressed so far the effect of a judicial officer's Facebook "friendships". However, some United States courts have observed that the mere fact of a Facebook friendship between a judge and a person involved in a trial before that judge does not, of itself, give rise to a perception of bias or warrant recusal. The Third District Court of Appeals in Miami, Florida, recently dealt with a Facebook friendship between a judge and an attorney acting for a defendant. That Court, which like the judge concerned, is elected, appeared to recognise that such social media connections do not necessary imply close friendship or affiliation. They considered that recusal would only be necessary when the friendship was so close that reasonable members of the public would question the impartiality of the judge[29].

34. Further, posts or comments that a judge makes on social media, even to his or her private circle, are inherently public. They can be easily disseminated by the judge's electronically-classified "friends" and cause embarrassment to the judge or Court. Appreciation by judges of social media, its dangers and its use is important. Last year the Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration and the Judicial Conference of Australia held a joint Symposium on Challenges of Social Media for Courts and Tribunals. I am not aware of any reports of Australian judges using social media inappropriately[30]. However, the same cannot be said of some American judicial officers.

35. In 2016, the Kentucky Judicial Conduct Commission brought proceedings against Judge Olu Stevens of the 30th Judicial Circuit for violating the Kentucky Code of Judicial Conduct. The charges alleged that the Judge made a series of comments on his Facebook page criticising the County's prosecutor. The impugned posts included statements that, "… [the prosecutor] has called me a racist. And set the media on me to deceive the people while he does his deeds. If people, particularly affected people, would stand up and call him out, he would go right back into the corner", and that "…The Jefferson Commonwealth's Attorney is for all white jury panels…"[31]. The proceedings eventually resolved when Judge Stevens agreed that he had posted those statements on Facebook and that had violated the Code of Judicial Conduct. He agreed to an order that he be suspended from his duties without pay for 90 days[32].

Australian lawyers

36. Social media also can shape or affect relationships and the nature of communications between lawyers, their clients and the general public. Members of the legal profession similarly ought to consider what impact the use of social media could have on their professional and ethical obligations. Those obligations affect a lawyer and judge in all aspects of his or her life and communication. Social media does not change that position even though persons often relax or drop their guard when expressing themselves on social media.

37. Potential employers now check an applicant's Facebook and other social media pages routinely before employing him or her. And, once the person begins work, employers have been known to monitor their employees' social media communications, particularly in relation to their views about their workplace, superiors, colleagues and activities.

38. Judges who use social media must also appreciate the potential for their postings to face similar scrutiny by the public. Unlike Spike Milligan's epitaph on his tombstone: "I told you I was ill", few people would find acceptable a judge or juror posting during a continuing trial a statement like: "He's guilty". The same caution applies to those acting in ongoing proceedings if they chose to use social media to discuss what is actually, or their perception or views about what is, occurring in the proceedings. That can cause a variety of problems, such as the disclosure of confidential information or information subject to legal professional privilege, or of material produced under compulsory process that is subject to the implied undertaking or obligation, as discussed in Hearne v Street[33], not to disclose such material other than for the purpose of the proceedings in which it is produced.

39. Lawyers' use of social media is governed by their ordinary professional and ethical obligations as members of the legal profession. There are no special exceptions or rules that apply uniquely to that space[34], other than the exercise of common sense. None of the Solicitor's Conduct Rules[35], Barristers Rules[36], or Legal Profession Uniform Law[37] address separately the use of social media. However, the Law Society of New South Wales has produced some Guidelines on Social Media Policies, developed by its Legal Technology Committee[38], and that State's Office of the Legal Services Commissioner has also published a Social Media Practice Note[39].

40. On 14 August 2015, Bellew J referred the question of a possible contempt of court, by a barrister, Charles Waterstreet, to the Registrar of the Common Law Division of the Supreme Court of New South Wales[40]. Mr Waterstreet was counsel for Glen McNamara, one of two accused former detectives in a murder trial. The question arose because of now suppressed evidence, to which his Honour referred, that Mr Waterstreet may have posted comments and photographs related to the trial on his Twitter and Instagram accounts[41]. Remarks that the same counsel had made in his opening address to the jury in an earlier trial of the two accused had caused Bellew J to discharge that jury two weeks earlier and a new trial was scheduled to commence on 18 August 2015. His Honour was hearing interlocutory issues pending the commencement of the new trial, when Mr Waterstreet's alleged social media activities came to notice. In the result, his Honour decided that the details of the comments and the photographs that Mr Waterstreet allegedly posted could not be published but that he had to order that the trial set to commence on 18 August 2015 be vacated.[42]

41. Again, in the United States, the Florida State Bar instituted disciplinary proceedings against a Florida lawyer who called a Fort Lauderdale judge an "Evil, Unfair Witch" on a popular legal blog. The lawyer after being found guilty of misconduct justifying bar discipline[43], agreed to a public reprimand and a fine, which was approved by the Florida Supreme Court[44].

42. So what is the approach that legal professionals should take to using social media? Probably not to emulate their American colleagues too closely. Again, as I said earlier, common sense and ordinary professional and ethical obligations govern all your activities as a lawyer and officer of the Court.

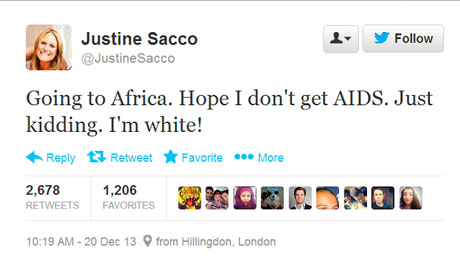

43. A professional career can be ruined by a careless or foolish tweet or post. One example of the disastrous effect such a communication can have is what happened to a public relations executive, Justine Sacco. She posted the following tweet to her 170 Twitter followers before she left London on a flight from New York to holiday in South Africa:

44. By the time her plane touched down in Cape Town, her tweet had gone viral and been retweeted tens of thousand times. A photographer snapped her in the arrivals hall. The next day, she was sacked from her employment. Her tweet created international outrage. She was denounced by the anonymous purveyors of social media correctness. Yet, when you think about what she did, it was to write a clumsy, silly joke. Had she said it in conversation with some friends, one or more may have said something discouraging, or she may have experienced an awkward silence or look. That would have made her realise that her comment was inappropriate. Or, her listeners may just have had a sense of humour, rather than outrage, and laughed.

45. Whatever may have been the outcome of a person to person situation, the use of social media and the retweeting with critical, if not denunciatory, comments created a virtual world lynch mob in which Ms Sacco could not be even perceived as having any amount of human frailty or a poor, but not malicious, sense of humour. Rather, she was vilified and became, for a time unemployable. And that was just because she wrote something silly as opposed to having constructed a deliberate campaign slogan for the Klu Klux Klan[45].

46. Things we used to say verbally as part of human communication to a small number of people can now become accessible, if said on social media, to millions instantaneously and in a permanent form. And, just as with direct face to face contact, posts can be misunderstood. Nor will the click of the delete button effectively erase an ill considered post – there is the earlier retweet or republication, not to mention the Wayback Machine to ensure that you cannot hide in the virtual world.

47. So while lawyers should not avoid social media, they would be well advised to consider carefully their choice of words and, when they publish, have regard to professional and ethical obligations as well as to common sense. In my generation, one commonly used test was to consider what would happen if what you were intending to write appeared on the front page of a daily newspaper – frequently it was a sobering idea.

The use of social media to criticise judges and courts

48. Social media also poses challenges for the rule of law and the maintenance of public confidence in the independence and integrity of the judiciary. An unfortunate trend is the use of social media to make inappropriate, populist or contemptuous attacks on individual judges or the judicial system as a whole. Normally each of the three arms of government is careful to respect the role of the other two, but we now live in interesting, and perhaps changing, times.

49. In times past, Attorneys-General saw it as their duty to respond robustly to inappropriate, populist or contemptuous attacks on individual judicial officers or the judiciary, including those made by our parliamentarians. Unfortunately, the political trend of recent years appears to be that Attorneys-General no longer see their role as such protectors of the judiciary from such populist attacks. This was one reason for the establishment of the Judicial Conference of Australia, as former Chief Justice French AC recently explained[46]. Earlier this year, three Federal government ministers issued tweets, and made comments to The Australian newspaper, that asserted that Victorian judges were handing down light sentences on terror as part of "ideological experiences" while the Victorian Court of Appeal was reserved on an appeal dealing with just such a sentence[47]. The Victorian Court of Appeal considered referring the ministers for prosecution for contempt of court because of their statements reported in the article, but decided not to proceed with the referral after the ministers apologised for their comments[48]. As the Court noted, the ministers' statements "failed to respect the doctrine of separation of powers", "breached the principle of sub judice" and "reflected a lack of proper understanding of the importance to our democracy of the independence of the judiciary from the political arms of government"[49].

50. Earlier this year President Trump tweeted his thoughts about a judge's decision that enjoined his Executive Order that restricted the ability of persons from seven countries to enter the United States. He tweeted:

51. Tweets like those of the President point to an ever-increasing challenge that courts and judges are facing – attacks on the judiciary in social media. Although such tweets can have unintended consequences. No doubt the President was even less delighted to see how the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals used those tweets to uphold a later injunction preventing a revised version of his ban from taking effect[50].

52. Another case of unintended consequences occurred in England. In February 2016, Judge Beverly Lunt sentenced two brothers, Daniel and Samuel Sledden, to suspended sentences of two years imprisonment on pleas of guilty to being concerned in the supply of cannabis. They had expressed their supposed remorse to her Honour which she had taken into account in her sentencing. But, forty minutes after being sentenced, Daniel wrote an obscene post about Judge Lunt on his Facebook wall, and soon after that his brother Samuel, wrote among other posts, "What a day its been Burnley Crown Court! ur … aha nice 2 year suspended"[51]. The posts were brought to her Honour's attention. Judge Lunt then recalled the brothers for a sentence review. She imposed sentences of two years imprisonment because of their Facebook posts[52], saying that the posts:

"were not private entries in a diary. They were placed on Facebook with the intention that others should and would read them and, if they wished, would share them. So it was a limitless audience"[53].

Judge Lunt added:

"The question I have to ask myself is this, if I had ...known their real feelings at being in court would I have accepted their remorse and contrition, and suspended the sentence. And the answer is of course not. Each of the posts indicate they have not changed at all. They have not taken on board anything or learned any responsibility."[54]

53. I am not suggesting for one moment that judges' decisions and conduct, both in and out of court, cannot or should not be scrutinised or criticised. It is a hallmark of our democracy that judges are accountable for their exercise of judicial power. That power is a public power of the State that regulates the rights of persons as against the state itself in criminal proceedings as well as, in civil proceedings, against other persons. In a real sense, every day a judge decides and declares what is the law that binds all persons in a society. A judge must sit in public when hearing proceedings in court and give public reasons for his or her decision.

54. Of course, judicial officers are public figures, and as I have acknowledged, they are publicly accountable for their decisions and conduct. That is as it should be in a democracy under the rule of law. But public accountability is very different to anonymous public vilification on social media of a judicial officer or a court. Freedom of speech and opinion are foundations of the rule of law. Our Constitution recognises an implied constitutional freedom for our society to communication government and political matters[55] that limits the power of Parliaments to make laws that affect that freedom of communication. The Courts are a governmental institution and people have a common law right to make fair reports of court proceedings, comment on them and criticise court decisions, but within limits[56].

55. Lord Atkin famously pronounced for the Privy Council in 1935[57]:

"But whether the authority and position of an individual judge, or the due administration of justice, is concerned, no wrong is committed by any member of the public who exercises the ordinary right of criticising, in good faith, in private or public, the public act done in the seat of justice. The path of criticism is a public way: the wrong headed are permitted to err therein: provided that members of the public abstain from imputing improper motives to those taking part in the administration of justice, and are genuinely exercising a right of criticism, and not acting in malice or attempting to impair the administration of justice, they are immune. Justice is not a cloistered virtue: she must be allowed to suffer the scrutiny and respectful, even though outspoken, comments of ordinary men." (emphasis added)

56. And in Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Wills[58], Mason CJ emphasised that the public interest lies in ensuring that courts and tribunals are open to "public scrutiny and criticism"[59].

57. However, the malicious use of social media to denigrate or threaten judicial officers poses challenges for the maintenance of public respect for the independence and integrity of the judiciary. Shortly after the tragic conclusion of the siege of the Lindt Café in Sydney, as President of the Judicial Conference of Australia, I had to issue a press release on 17 December 2014. Members of the mainstream media had contacted the secretary of the Judicial Conference drawing his attention to a threat against a magistrate that had appeared on social media. The social media critics asserted that virulent disagreement with the magistrate's decision to grant bail to Man Haron Monis. I said[60]:

That judicial officer was doing his or her job honestly and in good faith, as we all would expect.

The murderer will achieve his goal of dividing our society if the lives of judges and magistrates are threatened because they do their jobs as best they can.

58. That concern reflected the fact that a social media platform enables a user to post material that has the potential to reach an extremely large audience. The public dissemination of criticism in this manner can cause great harm. The concept in the title of Jon Ronson's book: "So You've Been Publicly Shamed" is a reality. Social media can make private individuals into instantaneous public figures, such as the unfortunate tweeter, Justine Sacco. In doing so it brings potentially enormous pressure to bear on the individual who is the subject. No one likes to be verbally attacked, even in a small meeting with just one other person present, let alone in a public meeting or context. But social media, even more than the old mass media, has a potentially huge audience – namely everyone who can access it. The personal pressure that an individual can feel from criticism on social media cannot be gainsaid. Imagine how that magistrate must have felt when learning of the threats. And, this pressure is not just felt by thin skinned individuals but by other persons in public life. Very recently the former Premier of New South Wales, Mike Baird, revealed to the Australian Financial Review that part of the reason behind his decision to resign and leave politics was that his school age daughters had been bullied on social media as a result of some of his controversial policies[61].

59. The law has very limited resources for dealing with social media attacks on persons including judicial officers. There are some possible avenues of redress for harmful social media publications. The Criminal Code (Cth) creates an offence punishable by a maximum of three years imprisonment for use of a carriage service in a way that the content of a communication would be regarded by reasonable persons in all the circumstances to be offensive[62]. There have been some prosecutions of this offence in respect of posts and messages about individuals (not judicial officers) on social media platforms like Facebook[63].

60. Another option may be to report abusive or harassing posts to the operator of social media platform on which they were posted and to seek their removal. However, for this to work, the offending content first must be in breach of the policies of the particular social media platform and the operator must then decide to act. Of course, there is no guarantee that the operator will assist in a timely manner, if at all.

61. The Australian Communications and Media Authority has power[64] to issue a take-down notice to a hosting service that hosts "prohibited content". However, that Act defines "prohibited content" as content that has been classified, or would be refused classification, as a restricted category, like an X rated movie, by the Australian Classification Board[65]. Whatever else one might think of nasty posts on social media about a judicial officer, the Authority's powers do not appear to apply to the usual stream of such malicious or threatening attacks, although the Sledden brothers' Facebook posts about Judge Lunt may have qualified because they had a vulgar sexual character.

62. Needless to say, judicial officers should be understandably cautious about exercising their inherent, implied or statutory powers to deal with personal or other attacks on them as contempts of court. And, it is unlikely that a judicial officer will sue for defamation about his or her conduct in office. Nonetheless, in O'Shane v Harbour Radio Pty Ltd[66] Beazley P, McColl JA and Tobias AJA, with Basten JA and MacCallum J dissenting, held that a judicial officer, Magistrate Pat O'Shane, had a private right of action to sue in defamation for statements made out of court. She has sued mass media publishers on more than one occasion with some success[67]. In the case cited, the majority of the Court of Appeal allowed her to continue proceedings against broadcaster Alan Jones. He had alleged that she had delivered "the most diabolical and wrong decisions" to which the defendants had pleaded truth. The possibility of a judicial officer conducting defamation proceedings with issues like those is daunting.

Conclusion

63. We cannot put the social media genie back in its bottle. Social media is now ingrained in the daily life of the community. Of course, its use by any section of society, including the courts or lawyers, cannot be ignored, let alone forbidden or discouraged. It will most often involve legitimate expression of opinion or communication criticising judicial decisions. But its continuing impact on our lives inevitably will lead to more challenges for courts and lawyers. Change while inevitable, has its challenges. In 1953, Denning LJ explained the amenability of judges to innovate when he said:

"What is the argument on the other side? Only this, that no case has been found in which it has been done before. The argument does not appear to me in the least. If we never do anything which has not been done before, we shall never get anywhere. The law will stand still while the rest of the world goes on, and that will be bad for both".[68]

64. The strength of the common law is its capacity to adapt to changing times and social conditions, including social media. But because social media is in the end a means of communication, hopefully its use will adapt in almost all contexts to respect the usual interpersonal constraints of decency and civility that ordinarily govern our other social interactions. To the extent it fails to do so and Parliaments do not act appropriately, the common law will develop remedies to maintain a balance to protect the rule of law and the independence and integrity of the judiciary.

[*] A judge of the Federal Court of Australia and an additional judge of the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory. The author acknowledges the assistance of his associate, Caitlin Healey-Nash, in the preparation of this paper. The errors are the author's alone.

A speech presented at the Australian Young Lawyers' Conference in Sydney on 20 October 2017.

[1] Jessica Taylor (@Jessica Taylor), "Help, @MerriamWebster. #Covfefe", 31 May 2017, 12:20am, Tweet. See further, Matt Flegenheimer, 'What's a "Covfefe"? Trump Tweet Unites a Bewildered Nation', New York Times (online), 31 May 2017 <https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/31/us/politics/covfefe-trump-twitter.html>

[2] Donald J Trump (@realDonaldTrump), 31 May 2017, 6:09am, Tweet

[3] Quoted in Flegenheimer, above n 1

[4] Dr Marilyn Bromberg-Krawitz, 'Challenges of Social Media for Courts and Tribunals', Issues Paper, The Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration and the Judicial Conference of Australia, 2016, p 2.

[5] Piyush Mangukiya, 'Social media by the numbers [Infographic]', Huffington Post (online), 25 April 2016 (updated 23 April 2017) <https://www.huffingtonpost.com/piyush-mangukiya/social-media-by-the-numbe_b_9757926.html>

[6] Peter Steiner, 'On the Internet, nobody knows you're a dog', cartoon, The New Yorker, 5 July 1993

[7] Judith Gibson, 'Social Media and the Electronic "New World" of Judges' (2016) 7(2) International Journal for Court Administration 1, 1

[8] Ibid

[9] Margaret Jackson and Marita Shelly, 'The Use of Social Media by Australian Courts', LexisNexis, 30 January 2016 <https://www.lexisnexis.com.au/en/insights-and-analysis/practice-intelligence/2017/30jan2017-the-use-of-social-media-by-australian-courts>

[10] Bromberg-Krawitz, above n 4, n 129

[11] AAP, 'Courts must use Facebook, Twitter to counter "skewing of information": Chief Justice' (1 September 2011) Sydney Morning Herald (online), 1 September 2011 <www.smh.com.au/technology/technology-news/courts-must-use-facebook-twitter-to-counter-skewing-of-information-chief-justice-20110901-1jmr1.html>

[12] Andrew Henderson, 'The High Court and the cocktail party from hell: Can social media improve community engagement with the courts?' (2016) 25 JJA 175, 175

[13] Gibson, above n 7, 1

[14] Alysia Blackham and George Williams, 'Australian Courts and Social Media' (2013) 38(3) Alternative Law Journal 170, 172

[15] Bromberg-Krawitz, above n 4, p 19

[16] Roadshow Films Pty Ltd v iiNet Limited (No 3) [2010] FCA 24 (Judgment Summary) [4]

[17] Supreme Court of Victoria, Media Policies and Practices, 2016, p 8

[18] Court Security Act 2005 (NSW) s 9A(10(b)

[19] Court Security Regulation 2016 (NSW) cl 6(a)

[20] Supreme Court Civil Rules 2006 (SA) r 9B; Supreme Court Criminal Rules 2014 (SA) r 12

[21] Reg v Young [1995] QB 324; see also Elizabeth Byrne, 'Can jury trials still be fair in the age of social media?', ABC News, 20 May 2017 <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-05-20/concern-over-jury-trials-in-internet-age/8543466>

[22] Alexandra Blucher, 'Gable Tostee juror's Instagram posts a sign Jury Act must roll with the times, legal experts say', ABC News, 21 October 2016 <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-10-21/tostee-juror-instagram-posts-sign-jury-act-needs-review/7952550>

[23] R v McManaman [2016] 1 WLR 1096

[24] Allsop CJ, 'Federal Court of Australia: Guidelines for Judges about using electronic social media', 6 December 2013

[25] Judiciary of England and Wales, UK Guide to Judicial Conduct 2016 (2016) <https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/publications/guide-to-judicial-conduct/>

[26] Maryland Judicial Ethics Committee, Issue: What are the restrictions on the use of social networking sites by judges?, Opinion Request Number: 2012-07, 12 June 2012, p 4

[27] (2000) 201 CLR 488 at 492 [11]

[28] Johnson v Johnson (2000) 201 CLR 488 at 493

[29] Law Offices of Herssein and Herssein, P.A. v United Services Automobile Association, No. 3D17-1421, 3rd District Court of Appeal, State of Florida [2017]

[30] Graham Maher and Sarah McCarthy, 'Social Media Friends without Privileges', The Australian (online), 27 September 2013 <http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/legal-affairs/social-media-friends-without-privileges/news-story/7309173a318688d2f75dbc2950e17aa6?nk=62ccd6de3c73e152e2dafc54e5460669-1508107963>

[31] Commonwealth of Kentucky Judicial Conduct Commission, In Re the Matter of: Olu A. Stevens, Circuit Court Judge, 30th Judicial Circuit, Amended Notice of Formal Proceedings and Charges, 21 March 2016

[32] Commonwealth of Kentucky Judicial Conduct Commission, In Re the Matter of: Olu A. Stevens, Circuit Court Judge, 30th Judicial Circuit, Agreed Order of Suspension, 8 August 2016

[33] (2008) 235 CLR 125 at 157-162 [155]-[113] per Hayne, Heydon and Crennan JJ

[34] Tahlia Gordon, Rita Schackel and Steve Mark, 'Regulation of Legal Services in the E-World: A Need to Short Circuit Hot Spots in Ethics and Novel Practices?' (2012) 19 International Journal of the Legal Profession 55, 78

[35] Legal Profession Uniform Law Australian Solicitors' Conduct Rules 2015

[36] Legal Profession Uniform Conduct (Barristers) Rules 2015

[37] Legal Profession Uniform Law 2014

[38] NSW Law Society, Guidelines on Social Media Policies, March 2012

[39] The Office of the Legal Services Commissioner, Social Media Practice Note, <http://www.olsc.nsw.gov.au/Pages/olsc_education/olsc_education_notes.aspx>

[40] R v Rogerson (No 14) [2015] NSWSC 1157 at [30]

[41] R v Rogerson (No 14) [2015] NSWSC 1157 at [5], [7]

[42] R v Rogerson (No 14) [2015] NSWSC 1157 at [30]

[43] The Florida Bar v Conway, No. SC08-326 ,Report of Referee; see further, Benjamin Beezy, 'An Alternative Approach to Evaluating Attorney Speech Critical of the Judiciary: A Balancing of Court, Attorney, and Public Interests' (2011) 1 UC Irvine Law Review 1221

[44] The Florida Bar v Conway, 996 So. 2d 313 (Fla. 2008)

[45] see the account in Jon Ronson: So you've been publicly shamed (ebook, Riverhead Books, 31 March 2015)

[46] 'Seeing Visions and Dreaming Dreams', Judicial Conference of Australia Colloquium, 7 October 2016, Canberra

[47] DPP (Cth) v Besim [2017] VSCA 158. See further, Tom Cowie, 'Turnbull ministers delete tweets attacking Victorian judges over terror' Sydney Morning Herald, 20 June 2017 <http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/turnbull-ministers-delete-tweets-attacking-victorian-judges-over-terror-20170620-gwuweg.html>

[48] DPP (Cth) v Besim (No 2) [2017] VSCA 165 at [31] per Warren CJ, Weinberg and Kaye JJA

[49] [2017] VSCA 165 at [6] per Warren CJ, Weinberg and Kaye JJA

[50] Hawaii v Trump, No. 17-15589 (9th Cir. 2017) n 14

[51] 'Brothers jailed after mocking judge who let them off', The Telegraph, 26 February 2016 <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/law-and-order/12174825/Brothers-jailed-after-mocking-judge-who-let-them-off.html>

[52] Dr Marilyn Bromberg-Krawitz, 'Challenges of Social Media for Courts and Tribunals', Issues Paper, The Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration and the Judicial Conference of Australia, 2016, p 33

[53] Quoted in Press Association, 'Drug-Dealing Brothers Jailed After Mocking Judge on Facebook', The Guardian (online), 27 February 2016 <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/feb/26/drug-dealing-brothers-jailed-after-mocking-judge-on-facebook>

[54] Quoted in 'Brothers jailed after mocking judge who let them off', The Telegraph, 26 February 2016 <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/law-and-order/12174825/Brothers-jailed-after-mocking-judge-who-let-them-off.html>

[55] Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1997) 189 CLR 520; Brown v Tasmania [2017] HCA 43

[56] John Fairfax & Sons Ltd v Police Tribunal of New South Wales (1986) 5 NSWLR 465 at 481 per McHugh JA, Glass JA agreeing

[57] Ambard v Director of Public Prosecutions 1936] AC 322 at 335 (on behalf of himself, Lord Mangham and Sir Sidney Rowlatt)

[58] (1992) 177 CLR 1 at 33

[59] And, in 2005, Justice Sackville recognised that the judiciary itself can benefit from vigorous criticism: Ronald Sackville, 'How Fragile are the Courts? Freedom of Speech and Criticism of the Judiciary' (2005) 31(2) Monash University Law Review 191, 194.

Statement by the Hon Justice Steven Rares, President, Judicial Conference of Australia, Threats to the Rule of Law, 17 December 2014.

[61] Jennifer Hewett, 'From premier of NSW to NAB: what Mike Baird did next', Australian Financial Review, 5 October 2017 <http://www.afr.com/brand/afr-magazine/from-premier-of-nsw-to-nab-what-mike-baird-did-next-20170814-gxvuce>

[62] s 474.17

[63] R v Hampson [2011] QCA 132; Agostino v Cleaves [2010] ATSC 19

[64] Under cl 47 of Schedule 7 of the Broadcasting Services Act 1992 (Cth)

[65] Broadcasting Services Act 1992 (Cth), Sch 7, cl 47(1)-(2)

[66] (2013) 85 NSWLR 698

[67] John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd v O'Shane [2005] NSWCA 164, (2005) Aust Torts Rep 81-789; see too John Fairfax & Sons Ltd v Foord (1988) 12 NSWLR 706

[68] Packer v Packer [1954] P 15 at 22