Washington Diaries of Owen Dixon: Review by Justice Lee

Southern Highlands Newsletter #241

Among Australian lawyers of a certain age and cast of mind, Sir Owen Dixon, occupies a place roughly equivalent to God in a mediaeval monastery.

A random example of this reverence is a speech in 1986 by former Governor-General and High Court judge, Sir Ninian Stephen, at the University of Melbourne to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Dixon’s birth. The praise was unstinting. He was described as “quite simply, the University’s most distinguished graduate and the greatest of Australian lawyers; a man whose name is known and memory revered in all those innumerable jurisdictions around the world where the Common Law runs”. Another former High Court judge, W M C Gummow, a man not known for throwing around unmerited accolades, recently observed: “[Dixon’s] statements of principle on a range of subjects continue to be the starting point for the process of judicial determination”.

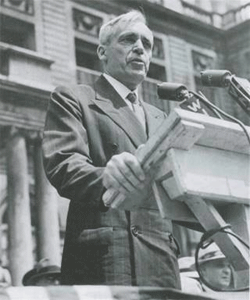

Owen Dixon in USA (from the Author’s collection)

A new book - The Washington Diaries of Owen Dixon 1942-1944, edited and annotated by Philip Ayers (Federation Press, 2020) - 392pp. incl index 19pp. - is a revelation primarily because its focus is on an aspect of Dixon’s professional life away from the storied discharge of his judicial function. Dixon was a Justice of the High Court between 1929 and 1964, the last twelve years as Chief Justice. This book is concerned with two critical years when Dixon took leave from the High Court to serve as Australia’s Minister to the United States, replacing Richard Casey, who then transferred to London to join Winston Churchill’s War Cabinet as its representative in the Middle East.

At this stage of Australia’s constitutional development, a judge acting in a diplomatic capacity seems decidedly odd. These were very different times. Nowadays the Chief Justice of the Federal Court makes it plain that federal judges should not even serve the executive government as Royal Commissioners, let alone fill positions for an extended period far removed from any judicial-type function.

In 1942, obtaining the permission of the Chief Justice was not difficult. That Chief Justice, Sir John Latham, had himself accepted appointment in 1940 as Australia’s first minister to Japan. He apparently had a long- standing interest in Japan. Given he reached Tokyo after Japan had concluded a pact of mutual assistance with the Axis powers, it was, one might think, not only a curious but a difficult mission. Luckily Latham was absent from Japan in September 1941 for consultations in Singapore, fell ill and was back in Melbourne before the unpleasantness at Pearl Harbor.

Back to Dixon. He left diaries - lots of them. No-one precisely knows why as he did not make any arrangements for them to be publicly available. An enquiry from the National Librarian in 1972 whether he would deposit his papers was met by terse refusal. The diaries survived. Leaving aside miscellaneous travel diaries, they cover 1911, part of 1929 and the years 1935-65. Fortunately, his daughter provided Dixon’s personal papers to Philip Ayres for four years for the purpose of Ayres writing his superb biography of Dixon published in 2003. Even more fortunately, he had them photocopied and deciphered.

It is important to recall that Dixon’s diplomatic role came at time when the Department of External Affairs was a quite recent development and was in a state of flux. Prior to the Statute of Westminster in 1931, ratified by Australia in 1942, Australia’s external affairs were conducted through the prism of the conception of an indivisible Empire. The Department was first given its own permanent head in 1935 but not until 1940 did Australia begin to establish overseas missions outside London. The first was in Washington.

The role was no doubt a delicate one. There was no well-established protocol of how to go about advancing the distinct interests of Australia, while at the same time recognising the need for solidarity with Imperial priorities as they were being advanced by Lord Halifax, UK Foreign Secretary. Halifax, an appeaser, came within a whisker of becoming prime minister in 1940. Churchill sent him out of harm’s way across the Atlantic. Harm, that is, to Churchill.

Evatt welcomes Dixon and family on return (from the Author’s

collection)

Dixon had a circuitous journey, arriving at the Legation on 2 June 1942 via a US Navy seaplane to Noumea (then under the administration of the Free French), Suva, the Christmas Islands, Hawaii, a Pan Am clipper to San Francisco, then American Airlines via Los Angeles, Tucson, Dallas and Nashville.

The arrival from London the same day of the Minister for External Affairs, Dr HV Evatt, was, as Ayers explains, a mixed blessing. Evatt introduced Dixon to important people; the downside was that Evatt was not well liked in Washington. He was perceived by many, including importantly Franklin Roosevelt’s closest adviser, Harry Hopkins, as an abrasive representative of an irritating mendicant.

This would not have come as a surprise to Dixon. Remarkably, he had been appointed by the Prime Minister, John Curtin, without any reference to Evatt. Dixon accepted on the proviso he was to communicate directly to the Prime Minister, bypassing the Minister.

In an earlier diary record of a conversation with Curtin, during which Dixon had suggested that the former Prime Minister, Lord Bruce of Melbourne be moved from London to Washington (with the intriguing suggestion Menzies be made High Commissioner), the following is recorded: “C. spoke of E’s character & so did I. I suggested C[asey] had resigned [as Minister to the US because of] Evatt”.

The author, in his detailed introduction, makes the point that the “part Evatt plays in these diaries is largely malign”. No doubt Evatt is portrayed in an unflattering light partly because Dixon never really liked him and grew to distrust his former judicial colleague, although, as Ayers point out, they retained a mutual intellectual respect (at least at this time).

Dixon was assisted by three future knights of high calibre. His first secretary was Alan Watt, who later became the first Australian ambassador to the USSR (and later Japan and Germany and High Commissioner to Singapore) and Secretary of the Department of External Affairs; his second secretary was Peter Heydon, who became our man in Brazil, India and New Zealand, a public servant of renown (and father of a future High Court judge); and as third secretary, Keith Aickin, Dixon’s former Associate and a future High Court judge, appointed to replace Sir Edward McTiernan, a contemporary of Evatt who Dixon considered lazy and unqualified but who had the good sense to default to the position of agreeing with Dixon.

Dixon arrived in Washington at a critical time. One of the revelations was just how testy the Australia-US relationship was when Dixon entered the scene. Australia had let its resentment of the “beat Hitler first” policy be known. As Ayers observes: “That objection got nowhere with the Americans, who pointed out how much was already being done for Australia, a country receiving tens of thousands of American conscripts from the other side of the world when its own laws forbade the sending of Australian conscripts beyond Australia’s territorial waters. This situation caused Dixon embarrassment but he was stuck with it. Time and again it would come up in conversations.”

Entries in the critical period of 1942 and 1943 are of particular interest. By April 1943, in a lunch meeting with Hopkins, it was made plain that Curtin’s messages “irritated the President, who no longer as formerly took trouble in answering them himself but flipped them over to someone else” and that Evatt made General Marshall and Admiral King “mad”. One entry in this period is remarkable. On 3 July 1942, Marshall recounted to Dixon a history of the engagements in the Coral Sea and at Midway “under a promise not to tell my government”.

Marshall is recorded as having said: “At one stage the Australian Government nearly destroyed Australia because they publicly said that Japanese forces had congregated in [the] Marshall Islands, a thing known only through breaking the Japanese cipher, as the Japanese must have been aware”.

Reading the diaries, one wonders whether, if someone less skilled than Dixon had been Australia’s representative, these irritations and tensions could have grown into a more serious problem.

Another revelation is Dixon’s access to the President, Hopkins and Marshall. I would be surprised if representatives of nations of comparable importance had anything like the access the diaries reveal.

Leaving aside the importance of the Pacific War, there is perhaps a less immediately obvious reason why FDR and Hopkins held Dixon in such regard. Dixon was liked and admired by Felix Frankfurter, whom he had met on his first full day in Washington. Frankfurter had been appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States by FDR in 1939 to fill the vacancy in what was later known as the “Jewish” seat caused by the death of Benjamin Cardozo. This tradition continued when Frankfurter eventually died in 1962; Arthur Goldberg succeeded him and then Abe Fortas succeeded Goldberg.

Frankfurter and FDR’s friendship was long and deep. Frankfurter had worked in the Navy Department when FDR had served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy before and during the First War (the role, incidentally, in which FDR met a person who later described himself in correspondence as a “Former Naval Person”, Winston Churchill). Frankfurter and FDR worked together regularly and maintained a causal friendship until FDR was elected Governor of New York in 1928, when the incumbent Al Smith ran for President.

At this time Frankfurter wrote: “Dear Franklin, Your victory is a great source of consolation and hope . . . you have . . . the conception of government which seems to me indispensable to the vitality of a democratic government, namely, the realization that the processes of government are essentially educational”. By the time FDR was re-elected in a landslide two years later, the friendship had become extremely close.

The benefit of a relationship to Frankfurter was obvious - FDR was already a leading contender for the Democratic nomination for President in 1932 - but from the perspective of FDR it was no less important. FDR obtained the assistance of a man he described as having “more ideas per minute than any man of my acquaintance” with “such a brilliant mind” that “clicks so fast” that “it makes my head fairly spin”. FDR found him “tremendously interesting and stimulating”.

Frankfurter, as a great lawyer, had a wide knowledge (uncommon in American jurists) of important cases in other common law jurisdictions and was familiar with Dixon’s reputation. As it happened, Frankfurter’s Australian interests were not confined to the law. According to one of Dixon’s successors, Sir Howard Beale, Ambassador 1958-64, Frankfurter possessed a surprisingly good knowledge of Australian parliamentary and political affairs. Interestingly, Frankfurter and Dixon shared a deep knowledge of the Classics.

Dixon’s forging of an immediate rapport with Frankfurter and earning his high respect was, one suspects, important to FDR and subordinates quickly developing an appreciation of Dixon’s talents and integrity. These personal relationships were greatly to the benefit of Australia at a critical time.

For all their considerable historical interest, and despite Dixon being apparently charming and adept in his personal interactions, Dixon’s diaries are somewhat chilly and distant. They reveal little of the man other than, as one reviewer of Ayers’ biography remarked, his “lofty superiority, some hypocrisy and a general malaise”.

One cannot help regretting that it is a pity that Dixon was not a different type of diarist. Many events which must have been of moment and encounters with persons of great historical interest are recorded in a taciturn, matter of fact way. A good example is an unlikely meeting in 1944 between Dixon and a man as different in temperament and standards of private conduct to him as one could imagine – Lyndon Johnson - the then representative of the 10th Congressional District of Texas.

No doubt many readers of this review would be familiar with the contours of LBJ’s life by 1944. He was an unabashed FDR admirer; had been a Congressman for seven years; three years earlier he had narrowly lost the Democratic U.S. Senate nomination in a special election to the sitting Governor and radio personality, “Pappy” O’Daniel, memorably portrayed in the Coen Brothers’ film, O Brother, Where Art Thou?.

Around two years earlier LBJ had been sent by FDR to report to General Douglas MacArthur in Brisbane to procure information on conditions in the Southwest Pacific. While on this mission, LBJ was involved in a forced landing of a Flying Fortress at sunset on a remote property near Winton and also volunteered to be an observer for an airstrike on New Guinea. The aircraft was allegedly attacked, disabling an engine. The aircraft turned back before reaching its objective.

Apparently to curry favour, MacArthur recommended Johnson for the Silver Star for gallantry in action: the only member of the crew to receive a decoration, which he proudly wore ever after. He was less than four years away from, but already planning, his highly controversial primary battle against Coke Stevenson. Oh, what stories that man could have told!

The relevant part of Dixon’s terse and anodyne entry for Friday, 26 May 1944 is as follows: “Evening, dinner by Office of War Information, Elmer Davis to Beasley. Sat next to Klauber and Thacker (Hawaii). Frankfurter also there, also Rep Johnson (Texas)”.

Vice-President Henry Wallace was a man one would expect to have been interesting. A former farmer and journalist, avid New Dealer, Wallace had served as Secretary of Agriculture from 1933 to 1940 until, overcoming strong opposition from party leaders, he was nominated for Vice President at the 1940 Democratic National Convention when FDR was nominated for his unprecedented third term. Part of Dixon’s diary entry for Thursday, 11 June 1942 was as follows: “Visited the Vice-President, Wallace. He had nothing to say”.

Nevertheless, what we have in Ayers’ book is both valuable and interesting. As these diaries reveal, Dixon was much more than a great lawyer. Perhaps this is something to do with the fact that he did not particularly like being a lawyer. It is said that he did not read another law report following his retirement in 1964, concentrating instead on reading and translating Greek and Latin classics.

His time in the USA and his other diplomatic adventure - appointment as United Nations mediator in the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan in 1950 - are important parts of the legacy of a great Australian. In editing and annotating these wartime diaries Professor Ayers has performed a valuable service.

Dixon presents James Cook’s Diary to FDR and

First Lady

(from the John Curtin Prime Ministerial

Library)