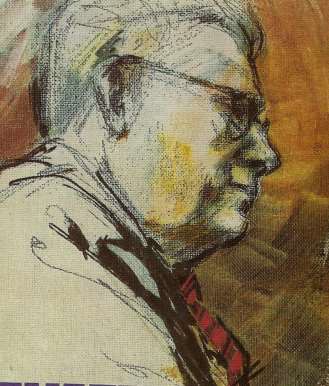

Evatt at his peak: Review essay by Justice Michael Lee

Gideon Haigh, The Brilliant Boy, Doc Evatt and the Great Australian Dissent (Scribner 2021)

Southern Highlands Newsletter #243

The “brilliant boy” of the title is not the Right Honourable Dr Herbert Vere Evatt, QC, PC. It is a lad of seven drowned on an otherwise uneventful Saturday afternoon in August 1937 in an eight-foot- deep trench filled with water in a Waverley street left unfenced by Council workmen. In the book’s opening pages, Haigh describes the working-class neighbourhood and the terrible events of that afternoon. Haigh is not the first to tell the tale.

Credit for a first evocative description belongs to Evatt. An irresistible combination of sand and water brought the children in the neighbourhood to play around that trench. The tragedies of little Maxie Chester and Golda, his mother, were first described by Evatt in his reasons in Chester v Council for the Municipality of Waverley (1939) 62 CLR 1.

Gideon Haigh has written what amounts to a short biography of Dr Evatt with a concentration on Evatt at the peak of his intellectual powers.

Evatt’s Chester judgement is very well known. It has long been lauded as one of Australia’s greatest judgements and has been the subject of recent commentary and analysis, including featuring in a fascinating compilation: Andrew Lynch (Ed.), Great Australian Dissents (Cambridge University Press 2016) pp.58-79.

To understand why the case merits such attention, it is necessary to understand a little about the law as it stood in the late 1930s. At the beginning of the decade, a case about a snail in a bottle of ginger beer had radically changed the law. Before 1932, the law of negligence had atrophied. Counsel running a novel negligence case looked to various relationships in which a duty to take care had been previously found to exist and then sought, by analogy to these categories, to bring the case within the reach of the law.

Haigh perceptively refers to the importance of a devout Anglican, the Brisbane-born Dick Atkin, in changing things. Ennobled as Baron Atkin of Aberdovey, he established that the Biblical injunction to love your neighbour becomes, in law, you must not injure your neighbour, and that the lawyer’s question “who is my neighbour?” should not receive a restricted reply. The law became: I owe a duty of care to those persons “who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question.”

In many cases the application of this principle is straightforward. Physical suffering was easy for the law to understand. Mental and psychological suffering presented greater challenges. What the High Court had to confront in Chester in 1939 was how Atkin’s insight was to operate in the circumstance where Golda, a mother, had suffered nervous shock, an abstract form of mental suffering, which arose because she had witnessed the recovery of Maxie’s body from the trench.

How Evatt approached this issue demonstrated an important facet of a highly complex man – his capacity for empathy. Understanding the plight of Golda was necessary to understand the nature of her loss.

The majority in the High Court concluded, in the words of the Chief Justice, Sir John Latham, that:

A reasonable person would not foresee that the negligence of the defendant towards the child would “so affect” a mother. A reasonable person would not antecedently expect that such a result would ensue. Death is not an infrequent event, and even violent and distressing deaths are not uncommon. It is, however, not a common experience of mankind that the spectacle, even of the sudden and distressing death of a child, produces any consequence of more than a temporary nature in the case of bystanders or even of close relatives who see the body after death has taken place.

Contrary to the misconceived view expressed recently by Geoffrey Robertson QC, Latham did not have a “second-rate mind”. As Sir Zelman Cowen noted, Latham had “highly developed powers of logical analysis”. In the Chester case, his logical but disengaged analysis was insufficient. Evatt was able to move past abstractions because he drew on the power of facts. He decided to detail graphically the events that afternoon: Golda’s long agony of waiting when she feared Maxie had been drowned, the impact upon her of Maxie being removed from the water without knowing whether he was dead or alive.

Evatt turned to the “very terrifying setting of the tragedy” and what must have been on Golda’s mind in the following terms. I quote Evatt at length in the sidebar accompanying this review.

Terrifying setting of tragedy.

Extract of Evatt judgment.

Like most mothers placed in a similar situation, she was tortured between the fear that he had been drowned and the hope that either he was not in the trench at all, or that, if he was, a quick recovery of his body and the immediate application of artificial respiration might still save him from death. In this agonized and distracted state of mind and body she remained for about half an hour, from when the police arrived and the child's body was discovered and removed.

During this crucial period the plaintiff’s condition of mind and nerve can be completely understood only by parents who have been placed in a similar agony of hope and fear with hope gradually decreasing. In the present case the half hour of waiting was the culmination of a long and almost frantic searching which had already reduced her to a state of nervous exhaustion. Even after the finding of the body, an attempt at artificial respiration was made and abandoned only after expert lifesavers had worked on the child’s body for some time.

William Blake's imaginative genius has well portrayed suffering and anxiety of this kind:—

“Tired and woe-begone Hoarse with making moan

...

Rising from unrest

The trembling woman prest With feet of weary woe:

She could no further go.”

The Australian novelist, Tom Collins, in Such is Life, has also described the agony of fearfulness caused by the search for a lost child:

“Longest night I ever passed, though it was one of the shortest in the year. Eyes burning for want of sleep, and couldn’t bear to lie down for a minute.

Wandering about for miles; listening; hearing something in the scrub, and finding it was only one of the other chaps, or some sheep. Thunder and lightning, on and off, all night; even two or three drops of rain, towards morning. Once I heard the howl of a dingo, and I thought of the little girl; lying worn-out, half-asleep and half-fainting—far more helpless than a sheep.”

At a later point, in the same novel:—

“There was a pause, broken by Stevenson, in a voice which brought constraint on us all. Bad enough to lose a youngster for a day or two, and find him alive and well; worse, beyond comparison, when he's found dead; but the most fearful thing of all is for a youngster to be lost in the bush, and never found, alive or dead.”

Not only its poets and novelists, but, at any rate in recent years, those engaged in the administration of the common law of England have recognised that shock of the most grievous character can be sustained in circumstances analogous to those of the present case.

In the circumstances, it is not remarkable that there was evidence of some permanent injury to the plaintiff's nervous system. According to the doctor who attended upon her:

“Time will heal it to a certain extent, but in her case the scar will be always there to a more extent than in the ordinary case of the ordinary death of a child, owing to the fact of her having seen the body as the boy was taken from the water and the fact that it was a tragic end, also the fact that this boy was a particularly brilliant boy and seemed to be the hope of her family, as she told me.”

Unlike the majority, Evatt’s close focus on the facts made the compelling case that a reasonable person would appreciate that the Council’s wrongdoing could have serious consequences on a person in the position of Golda. To suggest otherwise was not, as Latham would have it, “contradicted by all human experience” but rather reflected a more realistic and contemporary understanding of humanity. Haigh explains that Evatt’s view has been vindicated by history.

Haigh justifies his reputation as one of Australia’s finest and most eclectic writers of non-fiction. He appreciates that Evatt deserves reappraisal by focus on a time when he was most vital: bursting witha desire to make his mark internationally and beyond what he came to see as the limiting and provincial confines of the law. Using the case of Chester as a vehicle for this re-examination is highly imaginative and, for a non-lawyer, an intrepid task. Haigh succeeds.

The picture of Evatt is complex. One of the curiosities of Evatt is that a man capable of such emotional insight could show such a lack of empathy in other contexts. He could often treat people very badly. Haigh explains how Evatt dealt with his retainers on the High Court. For example, he gave his Tipstaff “undignified tasks” like carrying Evatt’s daughter’s potty and treated him “with almost calculated disdain”.

It is fair to describe his dealings with others as Minister for External Affairs, a time of great accomplishment in many ways, as not reflecting Dale Carnegie-inspired interactions. As those reading previous book reviews in this Newsletter would be aware, his personal relationship with high officials in the United States government caused significant problems for his erstwhile High Court colleague, Sir Owen Dixon, when Dixon became Australia’s representative in the United States in 1942. (See “Washington Diaries of Owen Dixon” reviewed by Justice Lee in Newsletter no.241: Holiday 2021). Nor, at the risk of understatement, did Evatt demonstrate what we would now describe as “emotional intelligence” while he was leader of the opposition.

The book highlights how seminal Evatt’s sabbatical was from the High Court in 1938-39. The picture of the High Court during Evatt’s period has been told many times, a bizarre working environment marked by judges (other than the benign and self-effacing Mr Justice McTiernan) regarding their brethren as being personally offensive or inadequate or both. Escaping this internecine hostility would have been relief enough. By being abroad, Evatt considered himself to have had a triumph.

After time spent in Chamberlain’s London watching cricket, immersing himself with Labour intelligentsia and the art world, plus a lengthy sojourn in Paris, Evatt encountered the United States. He lectured at Harvard and Columbia and was apparently a star turn. Felix Frankfurter, who later became so important in elevating the profile of Dixon in Washington, apparently arranged for Evatt to meet President Franklin Roosevelt for a meeting of 40 minutes.

The thought an Australian Chief Justice, let alone a puisne judge of the High Court, could obtain a lengthy meeting with the President of the United States is inconceivable at any other time in the Court’s history. What is even more remarkable is Evatt’s chutzpah. He decided to write to FDR, explain he had taken soundings and recommended Frankfurter’s appointment to the Supreme Court. As Haigh rightly asks: who on earth did Evatt think he was?

For someone who had such an outsized perception of his role, it is hardly surprising that he considered he belonged on the world stage, shaping great events. Chester was one part of what he considered to be his legacy to the law. He resigned from the Court shortly thereafter.

Another creditable aspect of the book is to rescue from obscurity the role of Abe Landa. Landa - here I disclose a bias, for he is my wife’s grandfather - was a person of substance and significant achievement. Having joined the ALP at the age of 16, he entered Parliament as the member for Bondi in 1930, only to be swept away as part of the 31-seat loss by Labor at the election following the dismissal of Lang in May 1932. He had a close affinity with the eastern suburbs pre-war Jewish community. He was an imaginative solicitor with an understanding of how the law could be used as an instrument of social justice. He championed the cause of Golda Chester and others in similarly desperate circumstances. He was returned to Parliament in 1941 where he remained until 1965, resigning controversially to become Agent General in London on Liberal Premier Bob Askin’s recommendation, causing a by-election in Bondi and leading to his expulsion from the party, an event which caused him much sadness.

His manner of leaving should not obscure his achievements. In addition to promoting other legal reforms, he righted the wrong of Chester by ensuring the passage of legislation allowing persons suffering mental distress to recover damages. Landa was an important part of the awakening of Evatt to the cause of a Jewish homeland and remained an adviser to him in relation to an important part of Evatt’s achieve- ments that is beyond the scope of Haigh’s book.

They were the remarkable events by which Evatt, initially Chairman of the Ad Hoc Committee on the Palestinian Question, later as President of the General Assembly of the United Nations, demonstrated political skill in resisting efforts to scuttle partition. Evatt then successfully lobbied for the Assembly’s approval of partition (33 to 13 with 10 abstentions) and assisted in securing, in the last week of his presidency in March 1949, the admission of Israel to the United Nations.

Although this and other achievements of the Doc might have become obscured by reason of his less than adroit period as opposition leader and his sad time as Chief Justice of New South Wales, it is surely going much too far to suggest, as Haigh does, that it may be accurate to describe him as a “little known Australian”. There is no other opposition leader who failed to attain the ultimate prize, or Chief Justice of New South Wales, who has been the subject of four good biographies (and some not so good). Indeed, with the exception of Whitlam, Evatt has had probably more written about him by authors of quality than any other Australian political figure, including Menzies. If that amounts to his being little known, then almost all Australian public figures who lived prior to 1970 fall into the same category.

As far as I discovered, there is only one clanger.

In dealing with the time when Evatt became hell bent on re-entering politics, reference is made to Evatt’s dislike of Menzies. Haigh describes an occasion when the still relatively new prime minister caught up with Sir Owen Dixon and how Menzies’ old mentor “pressed him with the situation in Melbourne owing to press criticism of inaction”. The following sentence then appears: “Evatt was also increasingly transfixed by his sometime boss.”

I read this once. I read it again. I raised the passage with others who were reading the book. It appears that the reference is to Menzies. Haigh acknowledges that some legal academics and common lawyers assisted him with his task. For a non-lawyer, the way in which Haigh deals with the workings of the High Court and the law of torts and explains complexities to a general audience is extremely impressive. The notion that Evatt (or any other Federal judge) would ever regard themselves as being in a relationship with the executive whereby a Prime Minister or an Attorney-General could be described as their “boss” is anathema. Such a description is fundamentally inconsistent with how our legal system and Constitutional arrangements operate.

One can be too picky. Gideon Haigh is a writer with a hinterland matched by no other widely read Australian author. The book appears to be a commercial success – it deserves to be. It also deserves to live on as a valuable resource.

Research undertaken is deep and thoughtful. Aside from some acknowledgments and a detailed bibliography, the origins of specific references remain mysterious.

I suspect I am like many readers of biography or history who, when first picking up a new work, will dip into the index to discover those who play a role in the narrative. Frustratingly, there is no index. It is a reflection of how well researched the book is that time and again, I wished to discover the source for a comment previously obscure to me relating to Evatt’s personality or work. Instead of discovering, I experienced a degree of frustration.

Of many examples I could cite, I restrict myself to Dominic Sandbrook, Seasons in the Sun: the Battle for Britain, 1974-1979 (Allen Lane 2012). In that superb account of the Callaghan years the following index entry appears:

Thorpe, Jeremy

1979 Election

Contracts Gonorrhoea from Greek prostitute

Plans to have his ex-lover eaten by Florida alligators

Scandal Trial

Went ashore from sinking hovercraft Wilson

Almost everything one needs to know about the absurdity of Thorpe’s career as Liberal leader, at a pivotal point in Britain’s modern history, and his notoriety as an accused participant in a conspiracy to murder is captured by this short entry.

Not every index is of this quality, of course. Producing an index and footnotes is a worthy exercise because a scholarly apparatus will entertain and inform. More importantly, adequate referencing is the means by which a book becomes a useful tool for research and further inquiry for as long as the book is read.

This complaint should not detract unduly from a remarkable book. Is it too much to hope that some future edition may be enhanced by footnoting and an index?