Communication highways and AI: International responses to manipulated realities

Presented at the International JAG Conference

Synopsis: The presentation draws on historical events and early international conventions protecting global communication systems and the content of communications, to draw parallels with challenges facing the world in regulating deepfakes and illuminate the different contexts in which these issues are being considered today by the international community. The presentation will also pose the question of whether customary international law governing the legitimate use of ruses of war remain adequate in the face of these technological advances.

Introduction

The evolution of modern machine technologies began with the development in the 1940s and 1950s of “reactive machines” which respond to a limited set or combination of inputs. This technology in time was enhanced by the additional capacity, through the use of algorithms, for machines to learn and adapt by analysing patterns in data.[2] Most recently, systems commonly described as AI have massively expanded the capabilities of machine technologies. In broad terms, these systems “exhibit or simulate intelligent behaviour” based on predictive or probabilistic outputs.[3] While many applications of AI are designed for specific tasks such as an image recognition system to identify skin cancer,[4] General Purpose Artificial Intelligence Systems (GPAIS), which are trained on large data sets and have a wide range of intended and unintended potential uses, are now a reality. [5] Examples include GPT-4, Copilot, Claude and Google’s Bard.

The power of such systems in turn will be significantly enhanced with the development of quantum technologies. This critical emerging technology massively boosts computing power above what is achievable through classical computers[6] and will bring with it ever more powerful and secure global communication networks. As one commentator has said, “[r]ather than relying on traditional computing’s binary “bits”—switches denoted as 1s and 0s—quantum use multivariant “qubits” that exist in some percentage of both states simultaneously, akin to a coin spinning in midair. The result is exponentially boosted computing power as well as an enhanced ability to intuitively mimic natural processes that rarely conform to a binary form.”[7] The potential impact of quantum computing can be illustrated by the experimental integration of quantum and AI in China. It is reported that quantum physicist Pan Jianwei “has developed a Jiuzhang quantum computer that he claims can perform certain kinds of AI-related calculations some 180 million times faster than the world’s top supercomputer”.[8]

The development of these machine technologies has significant implications from a defence perspective. They afford opportunities for us to strengthen our defences by developing and utilising these technologies to support human decision-making and to increase our national security resilience. Further to these ends, Australia is working with universities, industry and its allies including the Quad (Australia, India, Japan and the UK) and AUKUS on developing quantum technologies.[9] For example, QuantX Labs is working with the Institute for Photonics and Advanced Sensing at Adelaide University on groundbreaking quantum sensors and clocks to support better navigation and surveillance capabilities for Defence. As a further example, in May 2024, the Australian Department of Defence announced that the Navy, utilising AI algorithms developed with AUKUS, was employing machine learning in “predicting and countering undersea threats, and AI-enabled drones conducting surface and sub-surface missions”.[10]

However, these technologies also create significant risks of harm including, in particular, for human rights, democratic systems and processes, and global peace and security. In this regard, the astronomical rate of change and scale of developments in machine technologies has hitherto outpaced the capacity of humankind to develop the regulatory frameworks within which such technologies should be designed, developed, deployed, used and decommissioned. This is so notwithstanding significant recent progress nationally and internationally in developing appropriate regulatory frameworks and policies.

It is therefore no overstatement to say that we are at a pivotal point in human history, confronted with the reality of machines of exceptional power which are capable of being harnessed for the betterment of humankind but also capable of great harm.

These capabilities are effectively supercharged by the means by which we communicate and share information in a digital world. It is upon these means that I will initially focus today. I will then turn to the particular risks of misinformation and disinformation in the context of modern means of communication, recent international responses to these risks, and how these issues intersect with customary international law principles governing ruses of war.

Early steps in the evolution of an interconnected world

I hope you will indulge me in taking a short diversion to another pivotal moment in the history of technology.

That moment is the completion of a submarine telegraph cable by the British Australian Telegraph Company from Port Darwin to Java in 1871.

In a contemporaneous account, William Brackley Wildey observed that Captain Halpin, who was in charge of the ships comprising the cable expedition, “announced from Java that the cable was complete and in perfect condition, and that telegraphic communication was established between Australia” and the rest of the world.[11] Shortly after these events, in 1873 the overland telegraph line from Adelaide to Palmerston (as Darwin was then known) was connected to the newly completed submarine cable at Port Darwin.[12] The vast distances which communications were required to travel within Australia, and from Australia to the rest of the world, could now be bridged in a matter of hours, instead of months. Australia was no longer truly an island.

Mr Wildey also wrote that:

It is a remarkable fact, that although the cable can be seen whilst the operators thereby receive and flash the news to the various colonies, yet not one atom of intelligence ever ekes out.11

Australians embraced this new technology, sending, by the late 1890s, more telegrams per person than any other country. This is despite each word costing the equivalent of a day’s wage for a labourer.[13] Their messages were translated into the combination, known as morse code, of dots, dashes and spaces representing letters of the alphabet and numbers, and were transmitted as electrical impulses to be decoded at the other end.

Ensuring that the lines of communication opened by this transformative new technology were protected required international cooperation. The cables crossed vast oceans to connect different nations and their then colonies around the globe. On 14 March 1884, the Convention for the Protection of Submarine Telegraph Cables was signed in Paris, coming into force not long thereafter in 1888.[14] Its parties included Russia and the United States of America. They also included the United Kingdom[15] and thereby applied to its then colonies of Queensland, South Australia and Victoria.

The emphasis in the 1888 Convention was upon protecting the submarine cables, with the Convention declaring that it was an offence to wilfully or negligently break or injure a submarine cable (Article II). Article X in turn afforded rights to officers of State parties to require another vessel suspected of committing an infraction to furnish evidence of its nationality, and offences were expected to be prosecuted domestically by the State parties under locally enacted laws.

Many years later on December 7, 1941, these same submarine cables carried an urgent and terrible message to be relayed to the Australian government. The US naval base at Pearl Harbour was under a surprise aerial attack by the Japanese. My grandfather, who was then employed by the Cable and Telegraph Company in Darwin, was the first person on Australian soil to receive that message. Two months later on 19 February 1942, Darwin itself, of course, came under attack by aircraft of the Japanese Imperial Navy.

Today over 98 percent of the world’s data travels along 485 submarine cables connecting all continents, with the exception of Antarctica, and spanning the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.[16] Australia currently owns or operates approximately 400,000km of these cables – sufficient, as one commentator has observed, to lap the world ten times over.[17] Further some of these cables have been laid thousands of metres below the surface of the ocean, with the cable which connects Australia to Guam crossing the deepest trench on earth. These cables may soon be used in conjunction with quantum technology, thereby delivering “completely secure, unhackable lines of communication”.[18] In 2023, for example, researchers tested a 224-km fibre-optic cable enabling quantum communications between Ireland and the UK.[19]

While the 1884 Convention remains in force, the protection of submarine cables and the freedom to lay and operate cables came to be primarily governed by the 1958 Geneva Conventions on the High Seas and the Continental Shelf, and in time by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). While the United States is not a party, there are 170 State parties[20] to UNCLOS including China, the Russian Federation, the EU, the UK and Australia.

Significantly, Article 113 of UNCLOS requires every State to adopt laws making it a punishable offence to break or injure submarine cables beneath the high seas, either wilfully or through culpable negligence. It also requires States to adopt laws and regulations to reimburse persons whose cable was broken or injured by someone who is subject to that State’s jurisdiction.[21]

Damage caused to undersea optic fibre cables from the anchor of a cargo ship recently attacked by Yemeni Houthi rebels in the Red Sea is an example of such risks, and highlights, as one commentator has said, “the complex interplay between geopolitical conflicts and the security of global internet infrastructure”.[22] Of greater long term concern are reports, including from NATO allies, of Russian naval activity in recent years in the vicinity of Western submarine cables, given Russia’s maritime capacity through its deep diving submarines to sever cables at depths where repairs would be extremely difficult,[23] as well as its capacity to tap undersea cables.[24]

As one commentator has observed, “[a]ny significant damage to [the global network of submarine cables] would threaten global trade, military readiness, logistics, and Internet connectivity”. [25] In this regard, the commentator referred to estimates of over $10 trillion in financial transactions, commercial payments, and trade operations undertaken via the internet globally every day.[26] There are also growing concerns that Russia may target submarine cables, among other critical infrastructure, “to disrupt life in the West and gain leverage over countries providing security assistance to Ukraine.” [27] In this regard, in June 2023 in the context of alleged Western complicity in sabotage of the Nord Stream undersea gas pipeline, the Deputy Head of the Russian Security Council, Dmitry Medvedev reportedly stated on his Telegram channel that Russia has “no remaining moral constraints to refrain from destroying the cable connections of our enemies laid on the ocean floor”.[28]

Recent technological developments and challenges

While established regulatory systems exist under international law for the protection of submarine cables, regulating the information which they transmit is far more complex.

From the time that Hitler came to power in 1933, the Nazi regime effectively harnessed the dual power of censorship and propaganda including through the broadcasting of Nazi speeches on radio and by making radios more affordable within Germany.[29] It is therefore no coincidence that the International Convention concerning the Use of Broadcasting in the Cause of Peace1936, apparently the first international attempt to regulate the content of mass communications, came into force in 1938 on the eve of the Second World War.[30] Among the small number of State parties were Great Britain, France, Norway, and Australia. By that Convention, the State parties undertook to prohibit transmissions likely to harm good international understanding by inciting the population to acts incompatible with the security of other State parties, or to war with other State parties. They also undertook, especially in times of crisis, to broadcast information concerning international relations, the accuracy of which was verified by those responsible for broadcasting the information.

Deepfakes, which “utilize a form of artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML) to create believable, realistic videos, pictures, audio, and text of events which never happened”[31] take the capacity to manipulate events to an entirely new level. They thereby facilitate the creation of misinformation and disinformation for distribution potentially to a global audience. This in turn, as the ABA Taskforce for American Democracy has recently explained, “can distort reality, undermine trust, and destroy reputations, with potentially dire consequences for democratic processes”. [32]

First, deepfake software now freely available online has the capacity to manipulate videos and recordings based on training from photographs, recordings and videos readily accessible on the internet such as on news sites and social media accounts. Improvements in deepfake technology also mean that it can be very difficult to differentiate between deepfakes and real audio recordings, photographs and videos. These difficulties are particularly acute currently with respect to face swap software and fake audio recordings.

Indeed, deepfakes can apparently now be used in real-time as if they are conducting a conversation on an online audio-visual platform with a human. Reportedly, for example, in September this year an “actor” used deepfake software to impersonate a Ukrainian diplomat in a pre-arranged Zoom call with a US Senator. So convincing was the deepfake that the US Senator became suspicious only when the actor acted out of character and started asking “politically charged questions in relation to the upcoming election”. As the notice issued by the Senate security office stated, the Zoom connection “appears to be a live audio-video connection that was consistent in appearance and sound to past encounters.”[33]

Secondly, the problem is not merely identifying the deepfake; it can be in believing what is real. In other words, as one leading commentator, Professor Lilian Edwards, has observed, “[t]he problem may not be so much the faked reality as the fact that real reality becomes plausibly deniable.” [34] This has also been described as the “‘liar’s dividend’, in which an increase in manipulated content leads to general skepticism of all media and makes it easier for people such as politicians to dismiss authentic images, audio or video as fake”.[35]

Thirdly, the risks posed by deepfakes to spread misinformation and disinformation are amplified by the environment in which modern communication takes place. Multiple terabits of data are transferred every second via communication highways comprising approximately 1.2 million km (745,000 miles) of submarine cables and 2,500 telecommunications satellites. Added to this, social media, news and other platforms facilitate the mass transmission of information, misinformation and disinformation globally by the roughly 5.3 billion internet users worldwide.[36] Furthermore, the ability to disseminate deepfakes en masse through multiple information sources makes them appear to be more credible and therefore more likely to be accepted as true.[37] The algorithms in search engines also create echo chambers, reinforcing views of users based on preferences disclosed by their past browser history, thereby among other things potentially providing an effective means whereby extremist views can be consolidated. Added to this, the Transatlantic Commission on Election Integrity has suggested that attempts to correct the record after dissemination of misinformation and disinformation is largely ineffective.[38] While some of the major players producing generative AI software such as OpenAI and Microsoft have put in place safeguards on what their software can be used to create, that is not the case for all developers; nor does it prevent users circumventing those safeguards.[39]

The increasing inability to differentiate between what is real and what is not is particularly chilling given existing conflicts, expanding foreign influence utilising AI, and the heightened risks to global peace and security which currently exist. Indeed, the Global Risks Report 2024 by the World Economic Forum placed the likely adverse impact of misinformation and disinformation over the next two years through the adverse use of AI as the most severe global risk to world stability, over such risks as extreme weather events and interstate armed conflict.[40]

A recent example of foreign actors using deepfakes to spread disinformation is the fake documentary called “Olympics has Fallen” narrated by an AI-generated audio of Tom Cruise and promoted by bogus five-star reviews from the New York Times and the BBC.[41] The fake video seeks to disparage the IOC. It was apparently produced by a Kremlin-linked group known as Storm-1679, being intended as part of an anti-Olympics campaign. This also included fake news broadcasts to spread fear of terrorist attacks at the Paris Olympics.

In August 2024, it is reported that the Chinese government was likely responsible for circulating a deepfake video of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr appearing to take illicit drugs in an apparent attempt to undermine support for him in the Philippines 2025 election.[42] The video was circulated shortly before the President’s State of the Nation Address in the context of a ‘standoff’ over China’s claims in the South China Sea.[43]

Further, in September this year the US Departments of Justice, State and Treasury announced co-ordinated actions to “aggressively counter” an extensive campaign by Kremlin-backed media executives and broadcasters to interfere with the Presidential elections.[44] One of the fake reports prompting this action may well have been the false report of the Ukrainian First Lady purchasing a rare sportscar with monies sourced from American military aid while vising Paris for D-Day commemorations. The story was picked up on social media by influencers and reportedly viewed by 6.5m people from the account of one X user and at least 12 million people from other accounts.[45]

Finally, and most recently, reports have emerged that Moldova’s presidential election and referendum held last Sunday (20 October 2024) on amending Moldova’s constitution to include the goal of EU accession were heavily influenced by Russian interference.[46] The nature of this disinformation was to propagate sexist and xenophobic attitudes. For example, deepfakes have emerged of Moldova’s incumbent president, Maia Sandu, resigning from office while wearing a hijab.[47]

The international community, through a variety of instruments, has recognised the urgent need to combat misinformation, disinformation, and hate speech facilitated by these new technologies in order to safeguard democratic systems and practices, human rights, and the rule of law. In launching the Global Principles for Information Integrity in June this year, the UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, emphasised the “grave harm to our world” through the spread of hatred and lies online, including putting UN humanitarian and peacekeeping operations at risk.[48]

The Bletchley Declaration signed last year by 27 States, including the UK and Australia, also expressly noted “the potential for unforeseen risks stemming from the capability to manipulate content or generate deceptive content”, and emphasised the urgent need to address those risks. In turn, the AI EU Act which came into force in August and the Council of Europe’s AI Framework Convention which opened for signature in September, identify potential risks and adverse impacts posed by AI to democratic processes, the rule of law and human rights as high. Both instruments require measures to be taken or implemented to assess and mitigate these and other high risks and adverse impacts throughout the lifecycle of AI systems.

The Framework Convention is of particular significance. This is because it is the first legally binding treaty to regulate AI and is intended to respond to the urgent need for a globally applicable legal framework. The Convention is open to signatories outside the EU and, among its first signatories are the UK and the US, as well as the EU. Further, while not yet a party, Australia was among the non-member States which comprised the intergovernmental body that prepared the treaty. Key themes include:

- assessing and mitigating the risks of AI throughout its lifecycle from the cradle to the grave – from design and development to decommissioning;

- addressing the use of AI in the public and private sectors;

- ensuring transparency and oversight of AI systems having regard to context and risks; and

- ensuring accountability and responsibility for adverse impacts including by adopting accessible and effective remedies for violations of human rights.

Excluded, however, from the scope of the Framework Convention are systems deployed in the protection of national security interests subject to ensuring respect for international law and democratic principles and practices, and matters relating to national defence (Art 3(2) and (4)).

This leads me to the last topic on which I will touch today – how these issues might intersect with international humanitarian law governing ruses of war.

Ruses of war

Ruses of war have a long history, with the earliest recorded example being the wooden horse gifted to the Trojans in which the Greeks had hidden the best of their warriors.

The Trojans, believing the horse to be a peace offering to the gods, brought the horse inside the city walls and celebrated their victory, as the Greek ships pretended to sail away. That night, the soldiers crept out and opened the city gates to the Greek army who had returned in their ships under cover of darkness. And so, according to Virgil’s Aeneid, the ten-year siege of Troy was broken and the city was taken and destroyed by the Greeks.

In October 1944, Hitler commissioned one of his top commandos, SS Lt Col Otto “Scarface” Skorzeny to organise a special task force of commandos for the special Ardennes offensive. The task force’s objective was to infiltrate through American lines and capture at least one bridge over the Meuse River, and to create confusion in the Allied rear. The special mission was known as Operation Greif which translates as the mythical bird known as a “griffin”. Members of the task force were trained in English, and in American mannerisms by watching American films and learning how to swear, slouch, loiter, and chew gum. They were also trained in the driving of American vehicles and the use of American weapons. They were instructed to avoid contact with enemy troops and to avoid combat so far as possible in achieving their objectives.

Skorzeny and members of the taskforce were subsequently charged before the US Military Court in Dachau with participating in the improper use of American uniforms by entering into combat so disguised and treacherously firing upon and killing members of the US armed forces. Skorzeny’s defence that his tactic was a legitimate ruse of war as he did not order his men to fight in combat while wearing US uniforms, was upheld. Skorzeny and his co-accuseds were acquitted of all charges.

The rule of customary international law that belligerents can lawfully employ ruses of war to obtain an advantage by misleading the enemy is recognised by article 37(2) of Additional ProtocolI to the Geneva Conventions.[49] Examples of ruses of war given by article 37 are “the use of camouflage, decoys, mock operations and misinformation.” However, the killing, injuring or capturing of an adversary “by resort to” perfidy is prohibited (Article 37(1) of Additional Protocol I). Perfidy is an act which invites the:

confidence of an adversary to lead him to believe that he is entitled to, or is obliged to accord, protection under the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, with the intent to betray that confidence.

An example of perfidy provided in article 37 is the “feigning of an intent to negotiate under a flag of truce or of surrender”.

The policy underlying the prohibition is to ensure that the protections afforded under international law are respected, and to prevent their dilution by parties fearing perfidious conduct by their adversaries.[50] Furthermore, at least where the treachery or perfidy results in the killing or serious wounding of individuals belonging to the hostile State, the conduct would constitute a war crime under the Statute of the International Criminal Court.

How then do the use of deepfakes in the context of cyber military operations fit within this framework?

It is to be expected that deepfakes will be used in devising ruses of war. For example, rather than hiding inside a wooden horse, modern soldiers could gain access to tactical intelligence such as enemy positions or locations by using deepfake technology to impersonate an authorised person. Alternatively, alongside dressing soldiers in enemy uniform, deepfake technology could be used to construct entire identities, and give the appearance of language skills, facilitating infiltration into enemy forces. It is now the technology, rather than the soldiers, who learn mannerisms, accents and behavioural attributes from movies and other source materials. And, whereas Skorzeny’s special unit were able to complete only rudimentary training within a six week period before deployment, AI is able to train from a vast array of source materials at lightning speed.

The use of these technologies in ways which raise questions as to their legitimacy as ruses of war is far from hypothetical. To take a recent example, on the evening of 18 February 2022, visitors to a reputable Ukrainian news website would have encountered a video of President Zelensky announcing that the war with Russia was over and Ukraine was surrendering.[51]

The International Group of Experts behind the Tallinn Manual 2.0 published in 2017, were agreed that the Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions apply during cyber operations. Specifically, with respect to ruses, the group of experts accepted that ruses of war are permitted in cyber operations, such as by: the “creation of a ‘dummy’ computer system simulating non-existence forces”; the “transmission of false information causing an opponent erroneously to believe operations are about to occur or are underway”; and “bogus orders purporting to have been issued by the enemy commander” (Rule 123(2)).

With respect to perfidy, they drafted the following rule:

In the conduct of hostilities involving cyber operations, it is prohibited to kill or injure an adversary by resort to perfidy…

This indicates, on its face, that the use of deepfakes as ruses of war, is not inherently unlawful under the existing framework. Rather, the majority of the International Group of Experts concluded that only perfidious acts which are intended to result in death or injury are prohibited by customary international law.

This could mean that deepfake operations, which are inherently non-kinetic, are less likely to be captured by the customary prohibition on perfidy. The extent to which they may fall foul of the prohibition will depend upon how broadly the requirement that the requisite harm occur “by resort to” perfidy is interpreted – a question about which there is some uncertainty. Does the requirement mean that there must be a direct and immediate temporal and identity connection between the forces engaged in perfidy and the forces who commit the hostile act? Or should the phrase be given a broad, purposive interpretation so that the question turns on whether “but for” the perfidy, the death, injury or capture would have occurred?

Furthermore, given the scale and rate at which deepfakes can be spread beyond an isolated military deception, questions arise as to whether such uses in the context of ruses of war may contravene the customary international law principle of distinction (recognised in by the ICJ in its advisory opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons).[52] That principle requires parties to a conflict to direct their operations only against military objectives.[53] Questions also arise as to whether deepfakes may in particular cases offend the rule of proportionality governing incidental harm to civilians and the obligation to take constant care to spare the civilian populations and individual civilians.[54]

Conclusion

In this rapidly changing world, the international community is grappling with technologies far beyond the imaginings of Captain Halpin when he announced the establishment of telegraphic communication from Australia to the rest of the world in 1871. The world has never been so interconnected and arguably, people never so disconnected as news and opinions circulate within the echo chambers of browser algorithms and social media. This interconnectedness for humanity carries with it risks of great harm by amplifying the impact of misinformation and disinformation particularly at a time of heightened international conflicts and tensions. It is also a year in which over 4.2 billion citizens have or will vote in elections in approximately 65 nations in the context of numerous reports of these new technologies being deployed by foreign actors to influence the outcomes of the elections in their own interests.

It is therefore clear that urgent international collaboration, information exchange and the development of applicable standards is needed to ensure that developments in technology are applied for the betterment of humankind while safeguarding our democratic systems and promoting global peace and security.

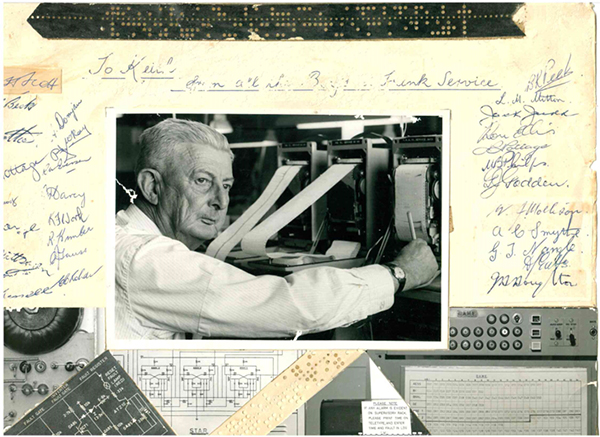

A collage given to my grandfather, Keith Goode, “from all the Boys in Trunk Service” on his retirement from the Cable and Telegraph company.

[1] Justice of the Federal Court of Australia; LLB (Hons, Adel), LLM, PhD (Cantab), FAAL. This article draws upon, and in part reproduces, material contained in the following: The Hon Justice Melissa Perry, ‘From Copper to Optic Fibre; Communication Highways and AI’ (Keynote Address, Launch of the International Digital Policy Observatory, 24 April 2024); and Tania Sourdin and Melissa Perry, “Introduction to the Special Issue on AI and the Law: Thinking about the Future of Justice”, (2024) 98 ALJ 631 at 633-637. The views expressed in this address are those of the author only.

[2] Naveen Joshi, ‘7 Types of Artificial Intelligence’, Forbes (19 June 2019) <https://www.forbes.com/sites/cognitiveworld/2019/06/19/7-types-of-artificial-intelligence/?sh=45f00d4a233e>.

[3] As defined in the Oxford English Dictionary (online): ‘artificial intelligence’.

[4] Future of Life Institute, General Purpose AI and the AI Act (May 2021).

[5] Future of Life Institute, General Purpose AI and the AI Act (May 2021).

[6] Charlie Campbell, ‘Gen AI Has Already Taken the World by Storm. Just Wait until It Gets a Quantum Boost’, Time (online, 13 May 2024) <https://time.com/6977355/generative-ai-quantum-computing-us-china-technology/>.

[7] Charlie Campbell, ‘Gen AI Has Already Taken the World by Storm. Just Wait until It Gets a Quantum Boost’, Time (online, 13 May 2024) <https://time.com/6977355/generative-ai-quantum-computing-us-china-technology/>.

[8] Charlie Campbell, ‘Gen AI Has Already Taken the World by Storm. Just Wait until It Gets a Quantum Boost’, Time (online, 13 May 2024) <https://time.com/6977355/generative-ai-quantum-computing-us-china-technology/>. See also Yu-Hao Deng et al, ‘Solving Graph Problems Using Gaussian Boson Sampling’ (2023) 130(19) Physical Review Letters <https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.130.190601>.

[9]National Quantum Strategy (Department of Industry, Science and Resources, 2023) pp 20, 31, 37, 38, 39, 41.

[10] Department of Defence, ‘Intelligent Tech for the Future’ (Media Release, 22 May 2024) <https://www.defence.gov.au/news-events/news/2024-05-22/intelligent-tech-future>.

[11] William Brackley Wildey, From Adelaide—Via Torres Straits—To Port Darwin, Thence Round West Australia (George Robertson, Melbourne, Sydney, and Adelaide, 1876) and reproduced online at: <https://atlantic-cable.com/Cables/1871Java-PortDarwin/index.htm>.

[12] ‘Defining moments; Overland telegraph’, National Museum of Australia <https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/overland-telegraph>; NBN Co, ‘The History of Telecommunications in Australia’ (Fact Sheet).

11 William Brackley Wildey, Australasia and the Oceanic Region, With Some Notice of New Guinea, From Adelaide—Via Torres Straits—To Port Darwin, Thence Round West Australia (George Robertson, 1876).

[13] ‘Defining moments; Overland telegraph’, National Museum of Australia <https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/overland-telegraph>.

[14] (1901) 1 ATS.

[15] ‘International Convention on the Protection of Submarine Cables, with additional Article’, Overheid.nl <https://verdragenbank.overheid.nl/en/Verdrag/Details/001885#Partijen>.

[16] Karen Scott, ‘Laws governing undersea cables have hardly changed since 1884 – Tonga is a reminder they need modernising’, The Conversation (21 January 2021) <https://theconversation.com/laws-governing-undersea-cables-have-hardly-changed-since-1884-tonga-is-a-reminder-they-need-modernising-175312>.

[17] Harry Tucker, ‘Keeping Australia connected to the world’, Telstra Exchange (22 November 2022) <https://www.telstra.com.au/exchange/keeping-australia-connected-to-the-world>.

[18] James Der Derian and Stuart Rollo, ‘Quantum Technologies: The Time to Discuss Risks is Now’ (online, 19 July 2024) <https://www.sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2024/07/19/quantum-technologies-time-to-discuss-risks-is-now-international-security-geopolitics-expert.html>.

[19] ‘Underwater Quantum Communications Tested between Ireland and the UK for the First Time’, Innovation News Network (4 October 2023) <https://www.innovationnewsnetwork.com/underwater-quantum-communications-tested-between-ireland-uk-for-first-time/37921/>.

[20] There are currently 170 States Parties as of 21 October 2024: <https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetailsIII.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXI-6&chapter=21&Temp=mtdsg3&clang=_en#1>.

[21] The importance of taking steps to mitigate the risks of damage to submarine telecommunications cables by Australia and the UK within their respective territories was also expressly recognised in Art 12.14 of the comprehensive Australia-UK Free Trade Agreement which came into effect in 2023.

[22] Robin Chataut, ‘Nearly all data that moves around the world goes through these undersea cables’, The Conversation (4 February 2024) <https://theconversation.com/undersea-cables-are-the-unseen-backbone-of-the-global-internet-226300>.

[23] Andrii Ryzhenko, ‘Russia looks to target Achilles’ heel of western economies on ocean floor’, Eurasia Daily Monitor 21(133) (17 September 2024) <https://jamestown.org/program/russia-looks-to-target-achilles-heel-of-western-economies-on-ocean-floor/>.

[24] See also Dr Sidharth Kaushal, ‘Stalking the Seabed: How Russis Targets Critical Undersea Infrastructure’, RUSI 25 May 2023 <https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/stalking-seabed-how-russia-targets-critical-undersea-infrastructure>; Victor Abramowicz, ‘Moscow’s Other Navy’, The Interpreter, Lowy Institute (21 June 2018) <https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/moscow-s-other-navy>.

[25] Andrii Ryzhenko, ‘Russia looks to target Achilles’ heel of western economies on ocean floor’, Eurasia Daily Monitor 21(133) (17 September 2024) <https://jamestown.org/program/russia-looks-to-target-achilles-heel-of-western-economies-on-ocean-floor/>.

[26] Andrii Ryzhenko, ‘Russia looks to target Achilles’ heel of western economies on ocean floor’, Eurasia Daily Monitor 21(133) (17 September 2024) <https://jamestown.org/program/russia-looks-to-target-achilles-heel-of-western-economies-on-ocean-floor/>.

[27] Andrii Ryzhenko, ‘Russia looks to target Achilles’ heel of western economies on ocean floor’, Eurasia Daily Monitor 21(133) (17 September 2024) <https://jamestown.org/program/russia-looks-to-target-achilles-heel-of-western-economies-on-ocean-floor/>.

[28] Andrii Ryzhenko, ‘Russia looks to target Achilles’ heel of western economies on ocean floor’, Eurasia Daily Monitor 21(133) (17 September 2024) <https://jamestown.org/program/russia-looks-to-target-achilles-heel-of-western-economies-on-ocean-floor/>. See also eg: Guy Faulconbridge, ‘Russia now has free hand to destroy undersea communications cables, Putin ally says’, Reuters (14 June 2023) <https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russias-medvedev-says-moscow-now-has-free-hand-destroy-enemies-undersea-2023-06-14/>; Christian Bueger, ‘Ukraine war: Kremlin’s threat to interfere with undersea data cables may be bluster, but must taken seriously’, The Conversation (21 June 2023) <https://theconversation.com/ukraine-war-kremlins-threat-to-interfere-with-undersea-data-cables-may-be-bluster-but-must-be-taken-seriously-208125>.

[29] United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Nazi Propaganda and Censorship’ <https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/nazi-propaganda-and-censorship?series=31>.

[30] 1938 LNTS 303.

[31] As explained, for example, in US Department of Homeland Security, Increasing Threat of Deep Fake Identities at p 3.

[32] N David Bleisch, ABA Task Force for American Democracy, ‘Deepfakes and American Elections’, ABA (6 May 2024) <https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_interest/election_law/american-democracy/our-work/deepfakes-american-elections/>.

[33] ‘US senator targeted by deepfake caller posing as Ukrainian diplomat’, The Guardian (26 September 2024) <https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/sep/26/ben-cardin-dmytro-kuleba-deepfake-ukraine>.

[34] Ian Sample, ‘What are deepfakes – and how can you spot them?’, The Guardian (13 January 2020) <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/jan/13/what-are-deepfakes-and-how-can-you-spot-them>.

[35] Nick Robins-Early, ‘Trump posts deepfakes of Swift, Harris and Musk in effort to shore up support’, The Guardian (20 August 2024) <https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/article/2024/aug/19/trump-ai-swift-harris-musk-deepfake-images>.

[36] R Limon, ‘Annual global data traffic equals 43 billion HD movies. How does it all flow?’, El Pais (4 May 2023) <https://english.elpais.com/science-tech/2023-05-04/annual-global-data-traffic-equals-43-billion-hd-movies-how-does-it-all-flow.html>.

[37] R Limon, ‘Annual global data traffic equals 43 billion HD movies. How does it all flow?’, El Pais (4 May 2023) <https://english.elpais.com/science-tech/2023-05-04/annual-global-data-traffic-equals-43-billion-hd-movies-how-does-it-all-flow.html>.

[38] Simon Parkin, ‘The rise of the deepfake and the threat to democracy’, The Guardian (22 June 2019) <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/ng-interactive/2019/jun/22/the-rise-of-the-deepfake-and-the-threat-to-democracy>.

[39] ‘Trump posts deepfakes of Swift, Harris and Musk in effort to shore up support’, The Guardian (20 August 2024) <https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/article/2024/aug/19/trump-ai-swift-harris-musk-deepfake-images>.

[40] Gayle Markovitz and Sophie Heading, ‘Global Risks Report 2024: The risks are growing – but so is our capacity t respond’, World Economic Forum (10 January 2024, updated 10 September 2024) <https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/01/global-risk-report-2024-risks-are-growing-but-theres-hope/>.

[41] Dan Milmo, Global Technology Editor, ‘Russia targets Paris Olympics with deepfake Tom Cruise video’, The Guardian (4 June 2024) <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/jun/03/russia-paris-olympics-deepfake-tom-cruise-video>.

[42] Albert Zhang, ‘China’s high stakes and deepfakes in the Philippines’, The Strategist (2 August 2024) <https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/chinas-high-stakes-and-deepfakes-in-the-philippines/>.

[43] Albert Zhang, ‘China’s high stakes and deepfakes in the Philippines’, The Strategist (2 August 2024) <https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/chinas-high-stakes-and-deepfakes-in-the-philippines/>.

[44] Sam Cabral, ‘US accuses Russia of 2024 election interference’, BBC (5 September 2024) <https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c8rx28v1vpro>.

[45] Paul Myers, Olga Robinson, Shayan Sardarizadeh and Mike Wendling, ‘A Bugatti car, a first lady and the fake stories aimed at Americans’, BBC (3 July 2024) <https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c72ver6172do>.

[46] Gabriel Gavin and Eva Hartog, ‘Moldova and Georgia ring alarm bells for the EU’, Politico (21 October 2024) <https://www.politico.eu/article/moldova-georgia-elections-eu-membership-referendum-russian-influence-kremlin-bribes-disinformation/>.

[47] Kristina Wilfore, ‘Battle for Moldova’s future: Gendered disinformation is Russia’s secret weapon’, Politico (18 October 2024) <https://www.politico.eu/article/moldova-elections-gender-russia-maia-sandu-europe-democracy/>.

[48] UN Sustainable Development Group, ‘Algorithms should not control what people see: UN Chief launches Global Principles for Information Integrity’ (24 June 2024) <https://unsdg.un.org/latest/stories/algorithms-should-not-control-what-people-see-un-chief-launches-global-principles>.

[49]Protocol additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12August 1949, and relating to the protection of victims of international armed conflicts (Protocol I), opened for signature 12December 1977, 1125 UNTS 3 (entered into force 7 December 1978).

[50] Mike Madden, ‘Of Wolves and Sheep: A Purposive Analysis of Perfidy Prohibitions in International Humanitarian Law’ (2012) 17(3) Journal of Conflict & Security Law 439, 450.

[51] John J Twomey, Conor Linehan and Gillian Murphy, ‘Deepfakes in Warfare: New Concerns Emerge from their Use around the Russian Invasion of Ukraine’, The Conversation (online, 27October 2023) <https://theconversation.com/deepfakes-in-warfare-new-concerns-emerge-from-their-use-around-the-russian-invasion-of-ukraine-216393>.

[52]Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons (Advisory Opinion) [1996] ICJ 3, [41].

[53]Tallinn Manual 2.0 (nxxi) 420–422.

[54] See further the discussion around these issues in the context of cyber operations in the Tallinn Manual 2.0 in the context of rules 93, 113, and 114-120.