Innovation and management of native title claims

What have the last 20 years taught us?

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

2013 National Native Title Conference

Alice Springs

By The Hon Justice Michael Barker

3-5 June 2013

1 I acknowledge the Central Arrertne people, the traditional owners of Alice Springs, and their elders past and present.

Land rights, Mabo and the Native Title Act

2 In the 1980s, as an academic at the ANU Law School in Canberra, I researched and wrote on the topic of Aboriginal land rights. I incorrectly predicted in the early 1980s that land rights was an idea whose time had come[1]. I thought it had. But the failure of the Western Australian Labor (Burke) Government to pass a statutory land rights scheme in 1985[2], and the subsequent failure of the Federal Labor (Hawke) Government to introduce a national land rights scheme as of 1986[3], put paid to the momentum that land rights had gained through the late 1970s and early 1980s.

3 I have always thought that these policy events were not unconnected with the ultimate preparedness of the High Court of Australia to rule, as it did on 3 June 1992 in Mabo[4], that native title had in fact survived the coming of the British sovereign into its new Australian colonies from 1788 onwards. Be that thought as it may, the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA) soon enough followed the decision in Mabo. And as was made abundantly clear by the time of the 2002 decision of the High Court in Ward[5], it is to the NTA, and not Mabo or the common law, that one must go to understand the metes and bounds of native title law in Australia.

4 The pioneering phase of native title was spent learning about these metes and bounds:

- From Western Australia v Commonwealth[6] we learned the NTA was (mostly) valid and that native title could exist throughout the continent of Australia, and not just in the Meriam Islands.

- From Wik v Queensland[7] we learned that native title could coexist with interests gained under such statutory tenures as pastoral leases.

- From Fejo v Northern Territory[8] we learned, however, that the grant of freehold totally extinguished native title. By that decision we were also introduced to the possibility that native title was not something holistic gained from occupation of land, according to traditional law and custom, but a collection or "bundle of rights" extinguishable wholly or partially.

- From Yanner v Eaton[9], on the other hand, we learned that a statutory declaration that fauna was "property" of the Crown did not necessarily extinguish native title and should be viewed as involving the regulation of the enjoyment of a native title right.

- From Commonwealth v Yarmirr[10] we found native title could be determined over the Australian territorial sea, although no exclusive possession rights could be derived over the sea, and no right to trade in the resources was discernible.

- From Western Australia v Ward, the concept was confirmed that native title is but a bundle of rights capable of total or partial extinguishment, and that a detailed determination of traditional rights is necessary in order to determine what particular rights and interests may have survived the grant of tenures under the general law.

- From Wilson v Anderson[11] we found that perpetual leases over the Western Division of New South Wales totally extinguished native title.

- From Yorta Yorta v Victoria[12] we learned that if the traditional laws and customs of a society from before sovereignty ceased at some point in time after sovereignty, a later adoption of them by a new society will not enliven the old laws and customs.

5 By about 2002, this pioneering phase came to an end and the rules governing native title appeared at least relatively settled, if not greeted with general approbation[13]. There has been and still is criticism concerning the rules governing proof of native title, the nature of native title, and how it may be extinguished. The rule that native title claimants bear the onus of proof in establishing their native title, rather than there being a presumption that they do which may be challenged by a respondent Commonwealth, State or Territory remains contentious[14]. There is also criticism that native title has been too narrowly defined as a collection of particular rights and interests, rather than as a broader community right for indigenous people to possess their traditional country. This particular criticism often finds voice in an indigenous complaint that holders of native title do not exercise anything approaching "sovereignty" over their traditional country[15]. Additionally, there are criticisms that the rules by which native title is extinguished are too broad, too absolute, too artificial. That traditional rights can be extinguished, for example, by the statutory process of resumption of a pastoral lease in order to create a national park is one example of this criticism[16]. There is also a broader policy critique that, where native title is found to exist, the benefits accruing to the holders of native title are unevenly distributed, depending on the extent to which the natural resources in country may be amenable to commercial or other exploitation[17]. Allied to this policy critique is the critique that, overall, some indigenous groups have been successful in having their traditional attachment to their country recognised, while many others have not been so lucky[18].

6 The dilemmas pointed to by these criticisms may be contrasted, at least in a theoretical way, with what the position of indigenous people in Australia might have been had a national system of statutory land rights, along the lines of that introduced into the Northern Territory by the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth), been introduced throughout the Commonwealth of Australia. But that is a topic for another day.

7 Nonetheless, in the last 20 years many applications for determination of native title have been processed successfully by claim groups under the NTA. Additionally, many parties to native title proceedings have made Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs) pursuant to the right to negotiate in respect of future acts given by the NTA.

Lessons from the past in managing claims today

8 The focus of my presentation today is on what lessons may be drawn from experience with native title claim management over the last 20 years and how they should inform the next phase of native title management by the Federal Court of Australia. This question is important because, as of last year, 2012, the Court has become responsible for the direct case management of all native title proceedings in a broader community climate where there is concern that the native title resolution processes are unnecessarily lengthy and expensive, rather than simpler and less costly. There is also a sense that "justice delayed is justice denied"[19].

9 During the pioneering native title phase, and indeed until 2012, innovation and management in native title management claims fell largely to the National Native Title Tribunal, with which, prior to the amendments of the NTA necessitated by the decision of the High Court in Brandy v Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission[20], claims were initially lodged and by whom they were mediated. From 30 September 1998, claims had to be filed in the Federal Court, but were required to be referred by the Court to the Tribunal for mediation. In 2012, the Tribunal's historic role as mediator of native title claims in effect ceased and was effectively transferred to the Court[21]. Nonetheless, the strong policy underlying the NTA at all times has been, and continues to be, that native title claims should be negotiated, and where possible the subject of consent determinations[22].

10 The steady flow of native title litigation in the Federal Court over 20 years, including in the 10 years since the end of the pioneering phase, suggests, however, that the resolution of claims by negotiated processes, whilst the preferred means of resolution, will not always occur and should not be seen as the only proper means of resolution of a claim. Indeed, experience shows that old issues continue to take on new forms. While "connection" disputes proliferated in the pioneering phase, they have not altogether ceased to be a feature on the recent native title landscape. The fact is that in areas of Australia where settlement by the British occurred earlier than in other areas, and where it was much more intensive than in other areas, connection has proved more difficult to establish, as the decision in Yorta Yorta perhaps demonstrates. But Yorta Yorta in many ways appears simply to have strengthened the resolve of many claim groups to prove their continuing connection as a society to their country. So experience teaches that connection doesn't necessarily become easier to resolve as an issue over time, and may well become more hotly disputed where the claim group is not as tradition-oriented as in some of the pioneering claims. Additionally, new extinguishment scenarios often require judicial determination. And now compensation claims, a relatively unchartered area for native title law, are beginning to be pursued[23].

11 Contested connection hearings are, however, time consuming and expensive. Experienced lawyers and anthropologists and other experts are usually involved in the proceeding. The pool of available expert witnesses has always been relatively small and, in recent years, has not been growing fast. Age perhaps has been wearying our experts, even if the years have not condemned them, and I suspect their pool requires refreshing!

12 Experience also teaches the fundamental importance of tenure analysis in relation to any claim. The fact that extinguishment may have occurred and be extensive does not necessarily mean that a claim group and a respondent government may not be able to successfully negotiate about a range of interests significant to the claimants and important to the governance of the jurisdiction in question. As originally drafted, the NTA contemplated a limited array of agreements, principally arising from the exercise of the right to negotiate provided by the NTA. With the 1998 amendments, the technique of the ILUA was introduced in a more formal way to deal with future act matters. Subsequently, in 2009, the power of the Federal Court to make a determination that dealt not only with native title outcomes but also with non-native title outcomes was conferred upon the Court[24]. Experience shows that while negotiations over a claim may start out about the existence of native title and the terms on which a consent determination might be made, the resolution of native title issues might be made possible by an agreement on related issues to do with cultural, heritage, land use and financial matters. Recent consent determinations providing for non-native title outcomes in the State of Victoria are in this respect highly instructive[25]. At the time of writing there are also well publicised negotiations occurring between the applicants, in what is generally called the single Nyoongar native title claim covering the south west region of Western Australia, and the State of Western Australia.

13 I should say, however, that the question of tenure analysis requires fresh and close consideration. It would be extremely useful to the early resolution of all claims if, contrary to the practice currently adopted whereby tenure analysis is usually conducted after connection issues are resolved, States and Territories were to undertake a tenure analysis as soon as possible after a claim has been lodged, if not beforehand. Once a tenure analysis has been made and settled by the parties, realistic assessments can be made on all sides about the extent to which native title is contestable. This would serve to inform the direction of negotiations over a claim made or likely to be made. The time is right for a new conversation about when tenure analysis should be conducted by a State or Territory; exactly what tenure needs to be analysed and at what depth; whether it is actually necessary, for the purpose of reliable negotiations and determinations under the NTA, to conduct an in depth analysis from the date of British settlement in respect of all grants, or whether a current tenure analysis will suffice in many circumstances; and whether the same type of tenure analysis is required in all cases.

14 This is a conversation that needs to be had, because the approach to tenure analysis usually taken under current approaches consumes an inordinate amount of time and money, comes late in the process and has the real potential to delay the resolution of native title claims or limit the options for their resolution. If, without compromising the outcomes of tenure analysis, a current tenure analysis different from that ordinarily made were capable of serving the purposes of all parties under the NTA, and could be completed more easily, cheaply and quickly, then why would it not be considered? That is the question.

15 Similar issues of utility arise in respect of the processes by which parties undertake in consideration of connection issues. One would like to think that the pioneering phase of native title has now passed, during which full-blown hearings on country to establish connection seemed inevitable. With the benefit of experience, aided by good legal and anthropological advice, States and Territories are now able to form sound judgments about when connection should be acknowledged. Again, the time taken to prepare for and conduct a full hearing on country in relation to connection issues is enormous and the costs associated with such litigation high. In terms of the judicial and staffing resources required of the Federal Court, the resource implications of such a hearing are huge. The question is, can not hearings, in most cases, be avoided by better disclosure and exchange of information in the pre-hearing stage of a claim?

16 In this regard, those experienced in native title may well agree with the proposition that, if only it were possible to get together the main anticipated witnesses in a proceeding, including anthropologists, at an early stage to discuss the essential features of the claim being advanced, then it ought to be possible for respondent States and Territories to more easily and more quickly come to grips with the evidentiary and conceptual nature of a claim and the prospects of success.

17 There has been a range of experiences as to the requirements of State and Territory governments when it comes to satisfaction of the connection issue. There is a danger they tend to become ritualistic, formulaic, cumbersome and bureaucratic; that they forsake flexibility for form. It is accepted all round that claim groups need to provide appropriate materials to State and Territory governments to satisfy them about connection matters, and that typically the information required will constitute both the anticipated direct evidence of Aboriginal people, as well as anthropological and related ethnographic materials to assist the State or Territory in their consideration of the connection claim. Flexibility as to what arrangement best suits a particular claim is plainly called for. There will, perhaps, always be an issue whether the dry, uncontextual reading of materials provided by an applicant, even when supplemented with videos and other visual aids, can ever be sufficient to convey to the reader the full significance of the material provided. For this reason, the Court has on occasion encouraged the taking of early evidence in a proceeding, whether by way of preservation evidence, the early commencement of a hearing or early meetings on country between the parties, to assist the connection assessment to be made.

18 On any of these approaches, claim groups and respondents need to be adequately prepared to engage in the required connection discussion and analysis. This leads to the additional lesson experience teaches: native title must be adequately resourced by governments to achieve what is achievable.

19 What I do not doubt, a lesson also readily taught by experience, is that the representatives of the parties engaged in native title do not lack the skill or the commitment essential to making the process work and work well.

20 Finally, it should be noted that the 1998 amendments also introduced the registration test to regulate the filing of native title claims, together with a requirement that applicants be authorised by the claim group as a whole to bring the application. These amendments were designed to minimise contested, overlapping claims and claims by persons who were but a subgroup of a larger group generally acknowledged to be the proper claimants. These provisions were also designed to better facilitate the exercise of the right to negotiate under the NTA and to eliminate the potential for the abuse of that right. These provisions, however, have produced their own subset of NTA litigation, with parties, both applicants and respondents, challenging decisions made by or on behalf of the Registrar under the NTA to register a claim or the fact of authorisation of a particular claim. Experience teaches that, while much has been done to minimise contesting claims by different Aboriginal groups to the same land, the circumstance of contested overlapping claims involving rival claim groups remains a feature of the native title system that requires careful management.

21 To draw to a close this survey of what 20 years experience with native title teaches in relation to the management of claims, it may be said the primary lessons to be learned are as follows:

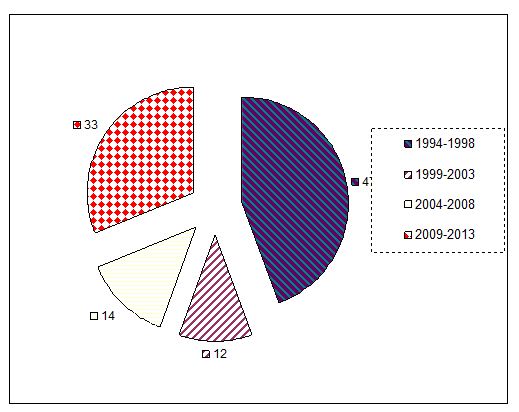

- The pioneering phase of native title claims, from 1994 through to 2002, involved extensive, intensive and expensive litigation in order to settle many of the rules governing native title.

- While it is reasonable to state that the rules governing native title are now largely settled, litigation has remained important not only in relation to unresolved connection and extinguishment issues, but also in relation to the developing area of NTA compensation.

- Nonetheless, negotiated, consent determinations of native title, to achieve both native title and non-native title outcomes, should now be seen, not merely as the preferred or ideal way to resolve native title claims, but the usual way.

- The commitment of parties and their representatives to good faith negotiations in respect of native title claims is undoubted.

- Nonetheless, the pool of experienced lawyers and expert anthropologists, important to the resolution of claims, if not critical, may not be bottomless.

- Claim negotiations are reliant on past practices which now require reconsideration in the light of a Court managed native title system.

- Adequate funding of the native title system to achieve timely native title outcomes is fundamental to the next, Court managed phase of native title resolution.

- The overall success of this next phase is highly dependent upon a tripartite endeavour involving the Federal Court, claim groups and their representatives, and respondent parties, especially governments, and their representatives.

Developing strategy to resolve native title claims in WA

22 In Western Australia, the Court is currently developing a strategy for the relatively early resolution of all native title proceedings currently listed in the Western Australian Registry. The strategy will be further developed and discussed with parties in the course of continuing case management.

23 However, essentially it involves profiling the current case load and identifying the cases that appear capable of resolution, on their face, by one process or another over the next three to four years.

24 The profile of current native title proceedings in the Western Australian Registry as of 31 May 2013, is as follows:

Number and by age: 106

Nature of Matters:

Applications for determination of native title – 102

Compensation applications – 4

Groups of related matters

Many of the 101 applications for determination of native title are related, and fall into the following number of sets of related proceedings – 56

Overlapping claims

Some claims involve contesting, rival claim groups – 26

Applicant representation

Applicants represented by a representative body – 85

Applicants represented by private lawyer – 12

Unrepresented applicants – 9

Respondent numbers

Least number of respondents in any proceeding – 1

Most number of respondents in a proceeding – 137

Average number of respondents in a proceeding – 21

Median number of respondents in a proceeding – 13

Matters in active case management

Whether before Judge or Registrar - 85

Matters in active mediation

Federal Court mediation – 11

National Native Title Tribunal mediation – 12

Other mediation – 1

Matters proposed for consent determination

Matters currently listed or expected to be listed for consent

determinations in 2013/2014 – 19

Matters proposed for contested hearing

Matters currently listed for contested hearing in 2013/2014 – 3

Other matters expected to be listed for contested hearing in 2013/2014 – 5

25 The developing strategy to facilitate the early resolution of these claims responds to the requirements of s 37M and s 37N of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), the detailed terms of which should be noted:

37M The overarching purpose of civil practice and procedure provisions

(1) The overarching purpose of the civil practice and procedure provisions is to facilitate the just resolution of disputes:

(a) according to law; and

(b) as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible.

(2) Without limiting the generality of subsection (1), the overarching purpose includes the following objectives:

(a) the just determination of all proceedings before the Court;

(b) the efficient use of the judicial and administrative resources available for the purposes of the Court;

(c) the efficient disposal of the Court's overall caseload;

(d) the disposal of all proceedings in a timely manner;

(e) the resolution of disputes at a cost that is proportionate to the importance and complexity of the matters in dispute.

(3) The civil practice and procedure provisions must be interpreted and applied, and any power conferred or duty imposed by them (including the power to make Rules of Court) must be exercised or carried out, in the way that best promotes the overarching purpose.

(4) The civil practice and procedure provisions are the following, so far as they apply in relation to civil proceedings:

(a) the Rules of Court made under this Act;

(b) any other provision made by or under this Act or any other Act with respect to the practice and procedure of the Court.

37N Parties to act consistently with the overarching purpose

(1) The parties to a civil proceeding before the Court must conduct the proceeding (including negotiations for settlement of the dispute to which the proceeding relates) in a way that is consistent with the overarching purpose.

(2) A party's lawyer must, in the conduct of a civil proceeding before the Court (including negotiations for settlement) on the party's behalf:

(a) take account of the duty imposed on the party by subsection (1); and

(b) assist the party to comply with the duty.

(3) The Court or a Judge may, for the purpose of enabling a party to comply with the duty imposed by subsection (1), require the party's lawyer to give the party an estimate of:

(a) the likely duration of the proceeding or part of the proceeding; and(4) In exercising the discretion to award costs in a civil proceeding, the Court or a Judge must take account of any failure to comply with the duty imposed by subsection (1) or (2).(b) the likely amount of costs that the party will have to pay in connection with the proceeding or part of the proceeding, including:

(i) the costs that the lawyer will charge to the party; and

(ii) any other costs that the party will have to pay in the event that the party is unsuccessful in the proceeding or part of the proceeding.

(5) If the Court or a Judge orders a lawyer to bear costs personally because of a failure to comply with the duty imposed by subsection (2), the lawyer must not recover the costs from his or her client.

26 In the current year 2013, the developing strategy contemplates that a range of matters are capable of being resolved by consent determination. The approach of the Court to those matters that parties agree appear likely to be resolved by consent determination is, and will continue to be, proactive. The judge responsible for the judicial case management of a proceeding will, where appropriate, request the parties to agree on the likely hearing date, on country or elsewhere, for the conduct of the consent determination hearing. Thereafter, the parties will be asked to lay out a program leading up to the hearing. This will be case managed by Registrars and case managers to encourage compliance. The process will involve the hands-on management of the proceeding by regular consultation with the parties to ensure that the consent determination is delivered on time. On this basis it is hoped that there will be consent determinations handed down in three related sets of matters in 2013[26]. The three related sets of matters would see the disposition of some seven separate proceedings in the current court list.

27 A further set of five related matters may also be resolved in the 2013 period or possibly 2014 period, once an issue concerning the existence of a native title right to trade in natural resources for commercial purposes, if it remains disputed, is resolved. The Court is taking steps to cause the early determination of that issue with a view, hopefully, to facilitating the consent determination of the various related proceedings. It is possible, therefore, that in 2013 this set of five related matters will also be resolved and removed from the current caseload.

28 There are five other separate proceedings that involve questions as to whether or not the proceeding should be dismissed for want of prosecution, or whether it should be dismissed because it has failed the registration test or because of some other particular legal issue, all of which are capable of early discrete determination. In each case the Court is proposing to list these matters for hearing and determination before a judge of the Court as soon as July 2013.

29 In three other continuing claim matters, early preservation evidence is to be taken or is likely to be taken during 2013.

30 There are yet other matters that involve major native title claims that are likely to be the subject of reserved judgments in 2013 or that will otherwise be resolved once appeal judgments have been delivered.

31 Another native title claim was listed for hearing in July 2013, but may, depending on final orders in the proceeding, now be resolved earlier during 2013 without the need for an extensive hearing.

32 In all there are some 30 separate proceedings that will be affected directly in 2013 by the Court's developing case management strategy.

33 In 2014, the strategy envisages that some 14 sets of related matters comprising some 48 separate proceedings are capable of resolution by a combination of consent determinations and agreements, determinations following hearings on country, and other hearings as required.

34 During 2013 and 2014 the strategy will be revised to ensure that active judicial and registrar case management focuses on key issues. One of the key issues, mentioned above, relates to the processes by which tenure analysis is completed. In Western Australia the Court will shortly convene a forum of native title users to discuss the tenure analysis process. The time is right for a conversation designed to identify new and more timely ways of conducting a tenure analysis. Presently there are a number of matters that should be resolved by consent determinations in 2014 that could be affected by any delay in the completion of tenure analysis.

35 If the strategy for resolution of native title proceedings in 2013 and 2014 were largely to be realised, there would be a balance of some 17 sets of matters comprising some 33 separate proceedings that would fall for resolution by early 2016. A number of these would presently be expected to be capable of resolution by consent determination. Others may be capable of a consent determination in respect of non-native title outcomes. In this regard it should be said that if the current negotiations on the single Nyoongar claim between the applicants and the State of Western Australia were to be brought to successful fruition in the foreseeable future, then the lessons to be learned from that process may well enable the successful resolution of not dissimilar native title claims in other parts of the State of Western Australia. It is possible that, in this period, other proceedings will need to be resolved after a hearing. However, on the face of it, the nature of the sets of claims falling into the 2015-2016 period, appear, by and large, to be capable of resolution by negotiation and consent determination.

36 The Court also desires to become more proactive in encouraging the resolution of claims by consent determination where, on the face of a claim, there appears a real likelihood of a negotiated outcome. In those cases, the Court would like to encourage negotiations at an early stage by the provision to the parties of a draft consent determination for consideration. The focus of the negotiation process thereafter would be on "Getting to Yes"[27].

37 So far as the developing strategy is concerned, the following things might be said by way of summary:

- The Court, with the encouragement of the Chief Justice of the Federal Court, desires to develop a strategy with a view to identifying the means by which and the timeframe within which the current native title caseload of the Western Australian Registry can be resolved with the application of adequate judicial and Court resources.

- Early strategy consideration suggests that the finalisation of the existing caseload, by one means or another, by mid-2016 is not unrealistic.

- The development of the strategy will occur during case management in discussions with the parties.

- The realisation of the strategy will require the active involvement of all parties involved in native title claims, especially applicants and their representatives, and representatives of the State of Western Australia.

- The strategy will necessarily involve new ways and new approaches to presentation and assessment of native title claims, both when negotiating connection and analysing tenure, and arriving at consent determinations.

- Early consideration will be given to streamlining the processes by which tenure analysis is conducted.

38 The new Court-managed phase of native title will be both demanding and exciting.

[1] Barker, M, "Aboriginal Land Rights Law in Australia: Current Issues and Legislative Solutions" [1984] AMPLA Yearbook 483.

[2] Seaman QC, P, The Aboriginal Land Inquiry (Government Printer, September 1984). The Aboriginal Lands Bill 1985 (WA) failed to pass the Legislative Council.

[3] Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, Submission No 3146 to Cabinet, National Aboriginal land rights legislation, 12 August 1985; Australia, House of Representatives, Debates (19 March 1986), p 1473.

[4] Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1.

[5] Western Australia v Ward [2002] HCA 28; (2002) 213 CLR 1.

[6] (1995) 183 CLR 373.

[7] (1996) 187 CLR 1.

[8] [1998] HCA 58; (1998) 195 CLR 96.

[9] [1999] HCA 53; (1999) 201 CLR 351.

[10] [2001] HCA 56; (2001) 208 CLR 1.

[11] [2002] HCA 29; (2002) 213 CLR 401.

[12] [2002] HCA 58; (2002) 214 CLR 422.

[13] Strelein, L, Compromised Jurisprudence (2nd ed, Aboriginal Studies Press, 2009).

[14] The Native Title Amendment (Reform) Bill (No 1) 2012 (Cth), a private member's Bill introduced by Senator Rachel Siewert and which is currently before the Senate, seeks to amend the NTA by reversing the onus of proof.

[15] Wensing, E, "Comparing Native Title and Anglo-Australian Land Law" (The Australia Institute, Discussion Paper Number 25, November 1999).

[16] See Western Australia v Ward [2002] HCA 28; (2002) 213 CLR 1 at [209]-[233] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ)

[17] AIATSIS Native Title Research Unit, Native Title Payments and Benefits: Literature Review (AIATSIS, August 2008), pp 9-20.

[18] Brennan, S, "Native Title and the Treaty Debate: What's the Connection?" (The University of New South Wales, The Treaty Projects Issues Paper No. 3, May 2004), p 7.

[19] Levinge v State of Queensland [2012] FCA 1321; (2012) 208 FCR 98 at [84]; Prior v State of Queensland (No 2) [2011] FCA 819 at [32].

[20] (1995) 183 CLR 245.

[21] Australian Government Portfolio Budget Statements 2012-13: budget related paper no. 1.2, Attorney-General's Portfolio, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2012, p 386.

[22] Explanatory Memorandum Part B, Native Title Bill 1993 (Cth), cf 65, Pt 4.

[23] State of Western Australia v Ward [2013] FCAFC 54

[24] Native Title Amendment Act 2009 (Cth) Sch 2 cl 5.

[25] See, for example, Mullet v State of Victoria [2010] FCA 1144; Lovett v State of Victoria [2007] FCA 474.

[26] Another set of related matters in the Martu proceedings having recently been the subject of consent determinations in late May 2013.

[27] See Fisher, R, Ury, W, Patton, B, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In (2nd ed, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1991).