Zen and the Art of Native Title Negotiation

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

2015 National Native Title Conference

Port Douglas

1 The best title of anything, ever, that I have come across is the title of Robert M Pirsig's 1974 book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.[1]

2 To quote the Wikipedia summary of the philosophical inquiry into values undertaken by the author: Pirsig explores the meaning and concept of quality, a term he deems to be indefinable. His thesis is that to truly experience quality one must both embrace and apply it as best fits the requirement of the situation.[2]

3 In the book, one guy, with an expensive new motorcycle, chooses not to learn how to maintain it, hoping for the best and relying on professional mechanics to repair it as and when required.

4 Another guy, with a cheaper, older bike, repairs it himself through the use of rational problem-solving skills.

5 So here we have a depiction of, on the one hand, those who romantically 'live in the moment' hoping for the best and, on the other, those who, by giving attention to detail, rely on rational analysis to solve problems and find beauty and inner peace of mind in doing so. Ultimately, Pirsig suggests that through a combination of rationality and romanticism we can achieve a higher quality of life.

6 And so I come to the subject of this presentation, which may be delivered, with appropriate acknowledgement to Pirsig, under the title, Zen and the Art of Native Title Negotiation.

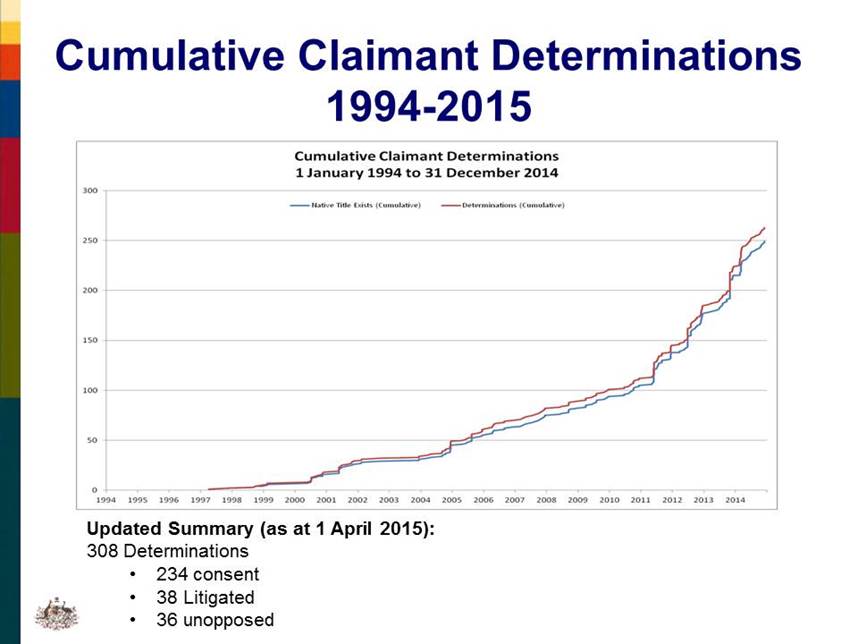

7 But, first, some statistics. Between 1994 and 2015 inclusive, there have been 234 consent determinations of native title made in the Federal Court. In that same period, there have been 38 litigated determinations [See first slide "Cumulative claimant determinations 1994-2015"]. Most of these determinations have been that native title exists.

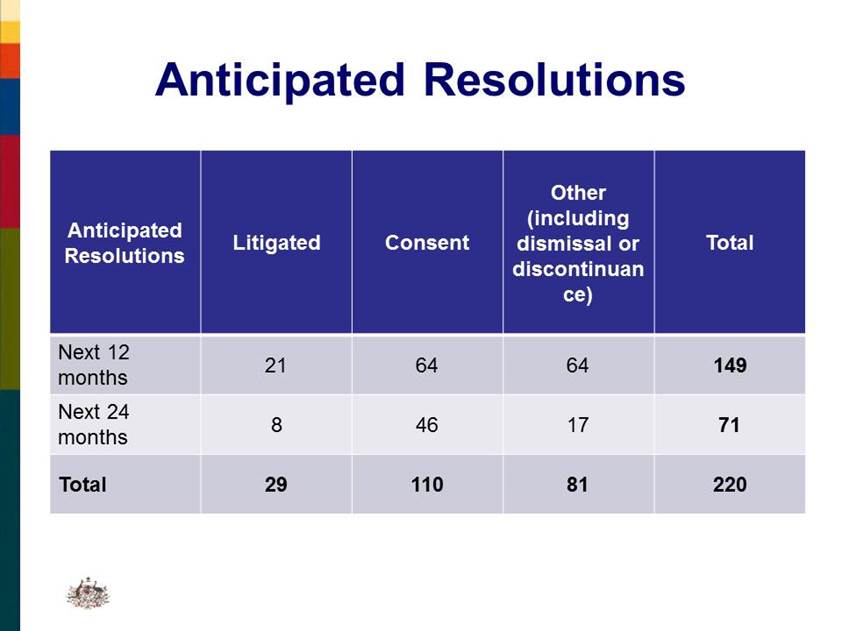

8 In 2015/2016 the Court anticipates a further 64 consent determinations and another 21 matters resolved through litigation. Additionally, the Court anticipates another 64 matters resolved by other means, including by dismissal or discontinuance. Over the course of 2016/2017, the Court anticipates an additional 46 matters resolved by consent, eight through litigation and another 17 by other means. [See slide "Anticipated resolutions"].

9 Obviously the challenges for the Court in resolving more matters, more quickly include: the resources available to the parties, both money and experts; tenure investigations; government policy – changes to native title representative body/service provider funding model; intra-indigenous disputation. [See slide "Challenges"]. To those I would also add what might be called "the changing focus of native title", which I will shortly explain.

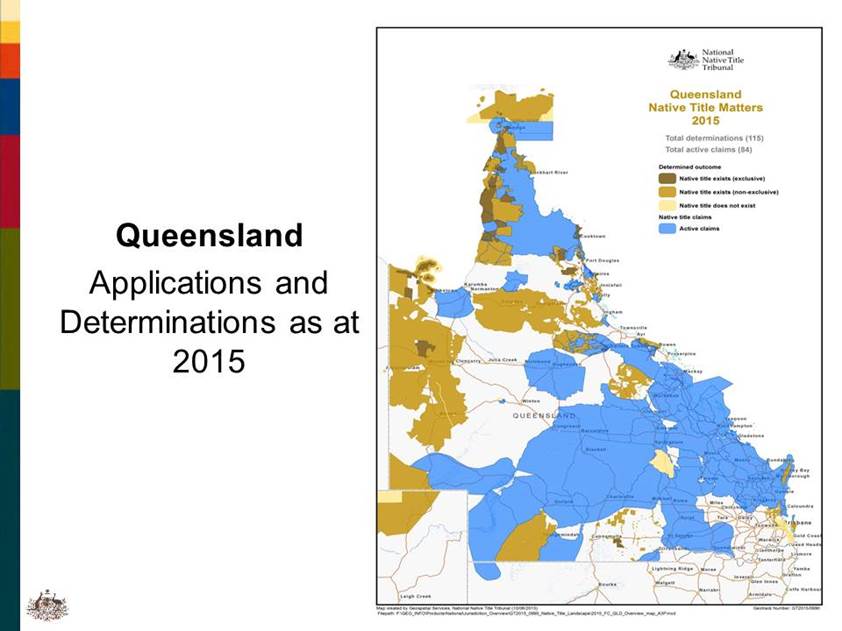

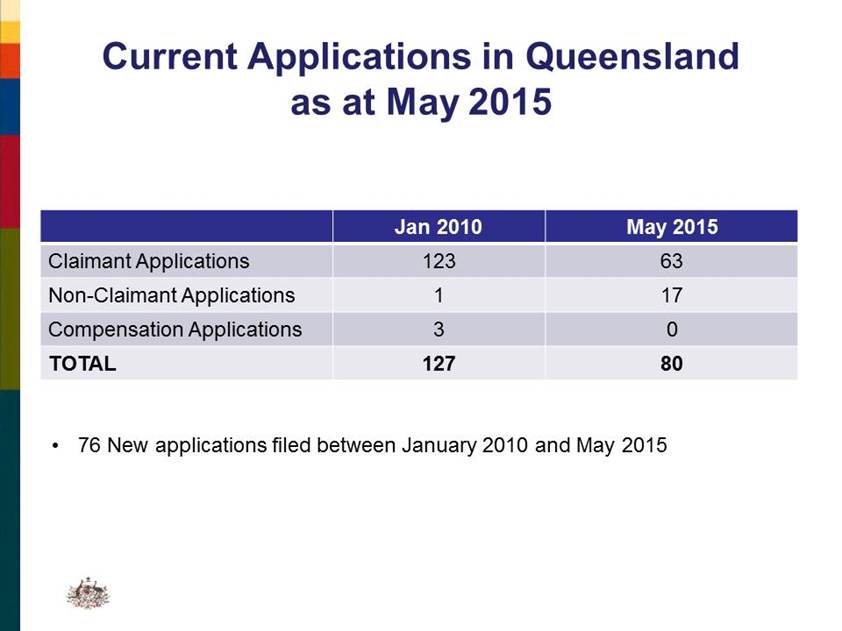

10 Queensland applications and determinations as at May 2015 may be considered of particular interest. [See slide " Queensland applications and determinations as at 2015"]. The blue areas show the active claims. As at May 2015, the active claims are 80 in total, including 63 claimant applications and 17 non-claimant applications. Between 2010 and 2015 there have been 78 new applications filed. [See slide "Current applications in Queensland as at May 2015"].

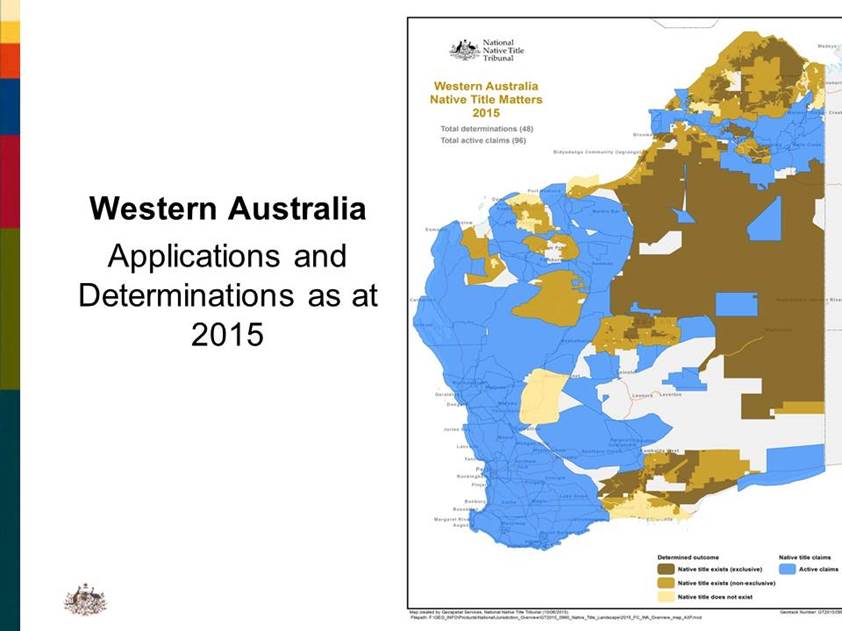

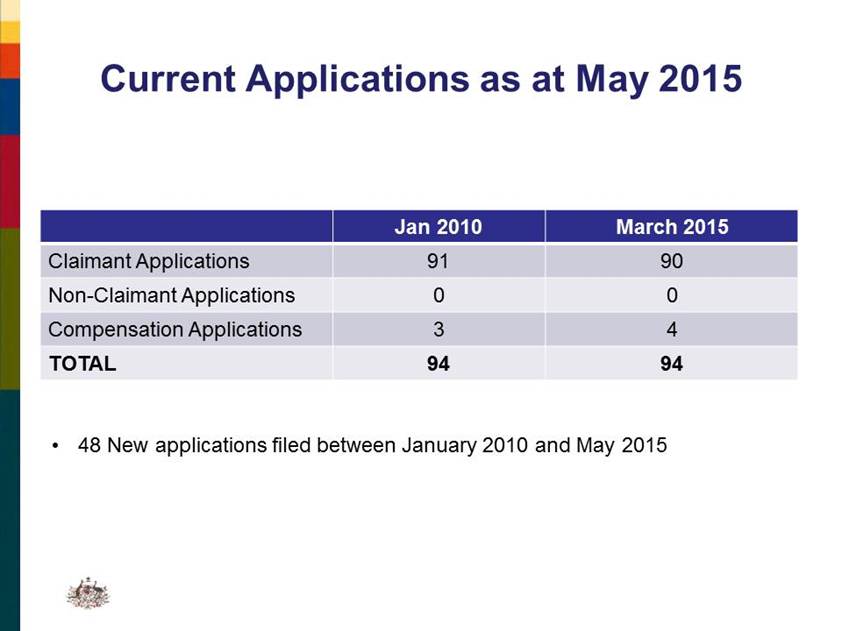

11 The position in Western Australia is not all that dissimilar. [See slide "Western Australia applications and determinations as at 2015"]. There are currently a total of 94 current applications, which include 90 claimant applications, no non-claimant applications and four compensation applications. [See slide "Current applications in Western Australia as at May 2015"].

12 The main differences between WA and Queensland as may be seen, are that WA has no non-claimant applications, whereas they are a feature and maybe a growing feature in Queensland; and there are no compensation applications in Queensland, whereas there are four in Western Australia.

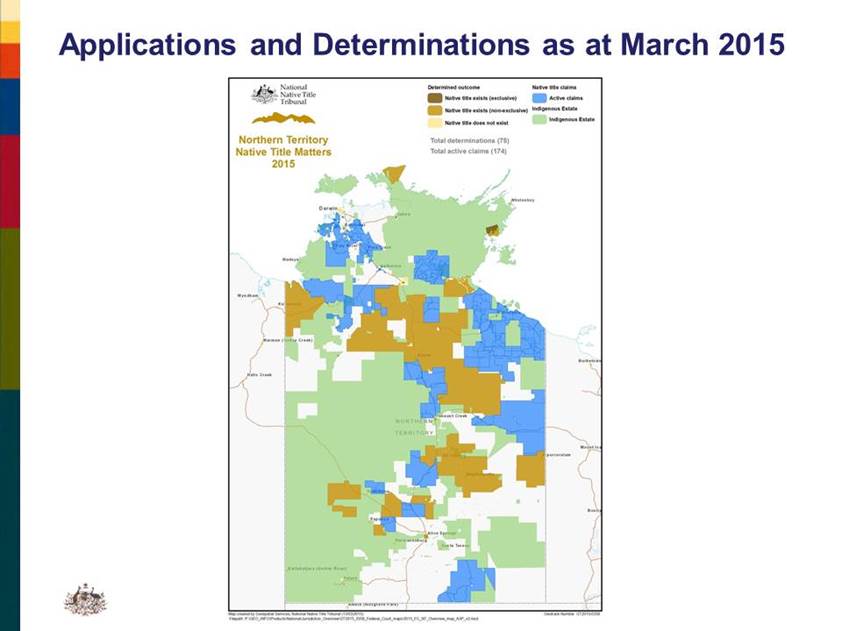

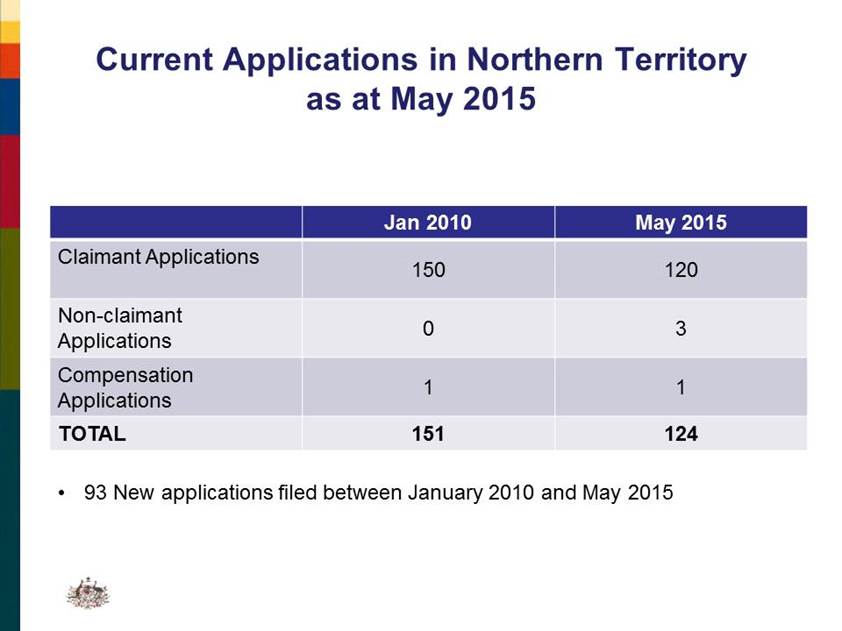

13 The position in the Northern Territory is not dissimilar to those two States.[See slide "Northern Territory applications and determinations as at March 2015"]. As at May 2015 there is a total of 124 current applications, comprising 120 claimant applications, three non-claimant applications and one compensation application. [See slide "Current applications in the Northern Territory as at May 2015"].

14 The position in the other States is significantly different. There are a total of only 23 current claimant applications in South Australia as at March 2015. In New South Wales there is a total of 25 current applications, comprising 19 claimant applications and six non-claimant applications. In Victoria there are only three claimant applications.

15 The immediate observations to be made, having regard to these statistics, are that:

- Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory continue to be "high volume" jurisdictions when it comes to proceedings in the Federal Court under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA).

- However, applications under the NTA in South Australia, and to a lesser extent New South Wales, continue to be of significance.

- The position in Victoria is that there is little NTA activity and, as mentioned below, this may be attributed not only to the decision of the High Court in Yorta Yorta,[3] but also to the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 (Vic) (Settlement Act) which, in effect, provides a State-based land rights system.

- The volume of applications and current applications in Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory suggest that applications for determinations of native title, non-claimant applications and compensation applications are not necessarily slowing.

- Consent determinations are the mechanisms by which most positive determinations are made that native title exists.

- Litigated claimant applications, however, continue to be a feature of the native title resolution process.

16 I do not intend to linger on litigated native title proceedings. There have in recent times been a range of contested determinations made by which the Court has determined that native title does not exist in Western Australia and Queensland. There has also been a recent contested decision in South Australia that native title does exist. As in the case of contested proceedings in the past, these recent decisions no doubt carry their own implications for the likely success of a range of claims that are currently before the Court but not currently in active litigation.

17 The other thing that might be said about these recent determinations is that the principles set by the High Court in Yorta Yorta as to proof of native title continue to resonate.

18 In that regard, mentioned should be made of the very recent publication, on 4 June 2015, of the Australian Law Reform Commission's (ALRC) recommendations for reform of the NTA, to be found in its report, Connection to Country: Review of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).[4] Connection recommendations include amending the native title definition considered in Yorta Yorta to clarify that:

- traditional laws and customs, under which native title rights and interests are possessed, may adapt, evolve or otherwise develop;

- acknowledgement of traditional laws and customs need not have continued substantially uninterrupted since sovereignty – nor is acknowledgement required by each generation;

- it is not necessary for the society, united by acknowledgement of traditional laws and customs, to have continued since sovereignty; and

- succession of native title rights and interests may be recognised.

19 It goes without saying that if the NTA were to be amended in these respects, the jurisprudence that currently controls the determination, and negotiation, of claimant applications would be significantly affected.

20 I do not, on this occasion, pause to consider those recommendations any further; or the likelihood of their legislative adoption.

21 What I do want to concentrate on in this presentation is the process by which decisions are made by parties to proceedings under the NTA as to how a matter may be, and can be, resolved – whether by a consent determination or through a contested hearing; or by other means, including through the use of an indigenous land use agreement (ILUA).

22 In my general assessment, borne out by the statistics I have just outlined, the approaches adopted by claimants, government parties and other respondents to proceedings under the NTA are very much a reflection of – not surprisingly – the native title experience of the last 20 years since the NTA came into operation at the beginning of 1994. In particular, the approaches of parties have been fashioned in the light of the landmark decisions of the High Court in Ward[5] and Yorta Yorta. Those cases laid down rules about the nature of native title and its content and extinguishment under the NTA, and the principles regarding the proof of native title under the NTA.

23 Those decisions led to the "bundle of rights" concept of native title and, so far as proof of native title is concerned, the concepts of "society" and adherence to laws and customs "generation by generation" since sovereignty.

24 In the early 2000s, following these decisions of the High Court in 2002, government parties such as Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia developed written guidelines to help structure dealings between claimants and the relevant government party with a view to exploring whether a determination might be achieved by consent – that is, whether a settlement could be achieved.

25 Under those guidelines, "connection reports" are typically provided by claimants to the government party, supported by anthropological information at an appropriate depth. Following consideration, and often the supply of any further information and some negotiation, the claimants and the government party arrive at a bilateral position. Typically, under the guidelines, the government party indicates its position and advises other respondents (such as pastoral interests, mining interests, fishing interests and the range of other interests typically involved in states such as Queensland and Western Australia) whether or not the government party is prepared to agree connection with the claimants.

26 Following the publication of the government party's position, other respondents typically are then engaged in the settlement process. Usually other respondents have been guided by the government party's position. They may have special interests, however, concerning the use of land and, over the course of the first decade of this century, those interests have led to ILUAs being made with the claimants at the same time as a consent determination is made.

27 The NTA provides expressly for consensual agreement making and litigated dispute resolution as mechanisms for resolving proceedings under the NTA. However, from the very beginning, the plan has been for parties to resolve as many matters as possible through consensual agreement making.

28 The statistics I have outlined above, do not include the number of ILUAs made throughout Australia that bear on, or potentially bear on, the resolution of native title matters. That is a large topic. Many presentations have been made on it in the past. Many ILUAs with large natural resource corporations are confidential, at least as to their fine details. So too are agreements made with other, smaller parties. It may be that some ILUAs have obviated the need for native title parties to pursue a claimant application or obtain a formal determination that they hold native title. To gain a full picture of the extent to which the NTA has produced final (and satisfactory) outcomes that achieve the broad objects of the NTA, one would need to know more about the ILUA situation.

29 One thing that is clear, however, is that the jurisprudence of Yorta Yorta means that not all claimants can and will succeed in obtaining either consent determinations or determinations following a contested hearing that they hold native title as defined. Even if the ALRC's recommendations were to be adopted, I think that would continue to be the case; although implementation of the recommendations may well remove a range of obstacles that currently lie in the way of claimants being successful in achieving either a consensual agreement with respondents or a determination from the Federal Court after a contested hearing.

30 One of the promises of native title, following the landmark decision of the High Court in Mabo,[6] was that not only would the traditional spiritual connection of indigenous people to their country, whether land or waters, be recognised and sustained in a post-sovereignty, modern Australian legal context, but also that the difficult economic and social situation in which many indigenous groups in Australia have found themselves for so long, would be remediated over time. The promise was that land and waters would enable communities to build strong economic bases with all of the educational and health advantages that usually flow from economic strength.

31 As we know native title has not been evenly distributed. Where it has been determined to exist, the fruits of native title in economic terms are also distributed in a patchy way. Not every holder of native title finishes up negotiating an ILUA with a large resource company (or a small one) authorising a future act on their traditional country.

32 The nature of native title, as a bundle of rights, and as an "inalienable title" is considered by some, perhaps many, to further limit the use to which those interests, that title, can be put. Will a bank lend money on the security of such title to permit native title holders to do the things that they might want to do on their country for their people? Should the law be changed to overcome or reduce the apparent burden of inalienability?[7]

33 As the first 20 years of experience under the NTA begins to recede behind us, the next 20 years opens up in front of us – particularly in front of those of you in the indigenous community and in all the professional communities that support all of the parties who become involved in matters arising under the NTA.

34 It seems to me that issues of connection and extinguishment, which have bedevilled, and continue on many occasions to bedevil, claimant applications under the NTA, should perhaps now be considered, not so much a thing of the past, but as only a part of the things that now need to be considered in the application of the NTA and in the approaches to be taken by parties to the resolution of applications under the NTA.

35 To make the point more boldly, if, even with the adoption of the recent recommendations of the ALRC, parties to a claimant application are not easily able to come to agreement on connection issues, and even if they are, why should not the parties seek to respond to an application by considering the range of other issues and interests that might be resolved between the parties? Such issues may go to the present and future relationship between the claimant group and the government party (and the citizens of the jurisdiction the government party is responsible for), including Aboriginal heritage issues, management of public lands, and compensation for past and future acts.

36 Why should not major players, such as large resource companies who have brokered a number of landmark ILUAs with claimant groups, prioritise the development of such agreements with claimants? And even if the government party appears to be proceeding at a slower pace in their negotiations with the claimants than that resource company respondent might think appropriate. In other words, why should not such a non-government respondent seek to take the lead in recognising and concluding arrangements with claimants to the extent that they can?

37 And why should not claimants assume full responsibility for the claims they have made and positively propose solutions to all respondent parties broader than merely the recognition of native title and the agreement of extinguishment? Why should claimants be constrained or feel constrained by the formal, published negotiating guidelines, where they exist, of government parties?

38 It seems to me, and this is the particular proposition that I wish to promote in this presentation, that we have now entered, in the second 20 years of the operation of the NTA, a subtly, but importantly different new era, where the resolution of native title applications needs to be approached more comprehensively, perhaps on a more regional basis and with a view in mind that the NTA is but an instrument enabling the settlement and realisation of legitimate and long-standing indigenous objectives.

39 In Australia at present, in each jurisdiction, save for Tasmania, in each of the States and the Northern Territory, there are reasonably settled, usual ways or approaches by which claimants and respondents deal with each other. I have outlined them in a primary way above. Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia have published guidelines which lay down the usual way in which claimants and the government party, in the first instance, deal with each other and explore whether a consent determination can be made or whether a matter must go to a contested hearing. Other respondents come in at the appropriate point. Tenure analysis is typically done once connection has been agreed and extinguishment issues are then resolved. It is all a slow and cumbersome and costly process. I have set out in appendices to this paper broad descriptions of the formal processes typically undertaken in each of these jurisdictions and I do not intend to labour them in this presentation.

40 Victoria is the most different, because of the Settlement Act. It enables a State-based land rights system to apply. It means that a more comprehensive resolution of indigenous claims to recognition and the management of land and waters potentially can be pursued. The appropriate people to claim can be identified. Questions of compensation as well as land vesting, management and heritage factors can all be taken into account.[8]

41 In many ways that system resembles the sort of settlements achieved under the Waitangi Tribunal resolutions and government/party agreements in New Zealand. New Zealand, in this regard, provides a conspicuous example of how indigenous and settler interests can be accommodated by not merely hoping for the best in achieving a good outcome, but by the exercise of rational problem-solving skills having regard to all the issues in contest.[9]

42 The proposed single Noongar settlement in Western Australia follows this same approach.[10] Under the terms of the South West Native Title Settlement, which includes ILUAs recently signed by the Premier of Western Australia and those authorised to do so on behalf of the negotiating claimants, a trust would be established into which $1.3 billion would be transferred over 12 years, including annual funding instalments of $50 million for 12 years, to support Noongar economic and cultural development. Up to 320,000 hectares of Crown land would also be transferred to the trust for cultural and economic development. One of the most significant aspects of the settlement would be the Recognition Bill which would recognise the Noongar people as the traditional owners of the south-west part of the State. In many respects this approach to the resolution of matters arising under the NTA reflects the range of issues to which I have referred above that fall into new era negotiations.

43 In this regard, the significant amendments made to the NTA by the Native Title Amendment Act 2009 (Cth) (Amendment Act) perhaps need to be revisited so that we are all reminded of how extensive the powers of the Federal Court now are in respect of matters arising within its jurisdiction. The Amendment Act effected changes to ss 87 and 87A of the NTA and in particular empowered the Court, whether or not a determination of native title is made, to make orders to give effect to the terms of an agreement between the parties that are about matters other than native title, even where only some of the parties are in agreement about the orders sought and even where a determination is only in respect of part of a claim area.

44 Justice Mansfield has made the following extra-judicial observations about these amendments:[11]

- Once it has jurisdiction over a matter by an application under s 61 of the NTA, the Court may make orders which give effect to terms agreed between the parties, even if there is no determination of native title as part of its orders.

- It is common for the Court to make orders which give effect to the agreement of the parties in terms which do not necessarily or obviously directly reflect the cause of action which primarily founds the jurisdiction of the Court, such as a compromise agreement between the parties that may be kept private and where the Court is simply asked to dismiss a proceeding once its terms have been complied with.

- There would appear to be no reason why once an application under s 61 is made, the agreed compromise of the matter should not be made effective by an appropriate order. Thus, in a compensation claim there may not be a determination of native title expressly made, but simply orders which give effect to the agreement as to the terms of compensation.

- Section 87(6) expressly extends the jurisdiction of the Court to make such orders once there is an application under s 61 to enliven its jurisdiction under s 81. The jurisdiction itself then extends to dealing with and giving effect to agreements that involve matters other than native title.

- Such an agreement may deal with matters specific to particular locations or sites, may deal with recognition of rights other than native title rights as described in s 223, may deal with employment opportunities, may deal with cultural heritage protection, or management of resources, or compensation or non-native title "recognition" or grants of land; or any combination of those matters, which is not intended to be a comprehensive list.

45 Much of the background to these 2009 amendments may be found in the "Guidelines for best practice, flexible and sustainable agreement making", developed by the Australian and State and Territory governments through the Joint Working Group on Indigenous Land Settlements in August 2009, which agreed:

- to develop innovative policy options for progressing native title through interest-based, negotiated settlements where possible;

- the native title system can facilitate broader settlement packages that offer a range of sustainable, tangible benefits for indigenous Australians;

- to establish and pursue jurisdiction-specific targets to benchmark progress; and

- to meet regularly to assess progress, share experiences and to develop a strategic approach for the effective resolution of native title.

46 Since these amendments in 2009, the Court has been in a position whereby orders made in a proceeding before the Court, under the NTA, can give effect to agreements reached by the parties and may do so whether or not there is in the proceeding a determination of native title over all or part of a claim area.

47 Despite the 2009 amendments, however, there have been very few, if any, orders made by the Court that explicitly rely on these powers.

48 My proposition is that, for all the reasons given above, it is important for claimants, government parties, and indeed other respondents to reflect on the range of outcomes that might be agreed in the course of negotiating the appropriate outcome to an application made to the Court under the NTA. That would assist in resolving the real demands of indigenous peoples for recognition of themselves as indigenous peoples and of their right to have an enduring relationship with and responsibility for their traditional country.

49 Having regard, to that introduction, I would now like to raise for discussion a number of topics about which, I should emphasise, neither the Court and its judges and registrars who are actively engaged in native title case management and mediation, nor I have any concluded views. Just as Mao Zedong famously declared, "let a hundred flowers bloom", in order to see which are capable of flourishing, I thus raise these topics purely to provoke thought and discussion.

50 I hasten to add that I do not think there are necessarily any "right" answers to any of these questions and that particular approaches will typically be recommended for dealing with particular issues, that flexibility is required, that no "one size fits all".

Do we still need "connection reports"?

51 As the accounts of indicative practices in each of the Australian States and the Northern Territory set out in the appendices indicate, Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia have published guidelines setting out how claimants and the government party should approach claim assessment. Western Australia no longer relies on the guidelines that it first produced in 2004, however the "Guidelines for the Provision of Connection Material" published in 2012 are still current. Other jurisdictions do not have published guidelines, although no doubt professionals engaged on behalf of parties dealing with s 61 applications have expectations as to how the process of negotiation should ordinarily work. The "connection report" has been a feature of dealings in the high volume jurisdictions of Queensland, Western Australia, Northern Territory and South Australia for some years, especially since the early 2000s.

52 A concern I have about any prescribed procedures, including guidelines and the provision of a "mandatory" connection report, is that parties, particularly claimants and the government party, at an early stage of negotiations, become slaves to procedure without paying adequate regard to substance and what is really in issue in each proceeding.

53 After 20 years of native title, it can no longer be said that government parties, for example, are lacking information of an ethnographic kind, an historical kind or in the other expert areas that perhaps they once were at the time early cases such as Ward and Yorta Yorta were litigated. Nor are claimants and their advisors any longer inexperienced in these matters, if once they were.

54 There is an appreciation that "native title anthropology" is different from "anthropology", at least the anthropology that was conducted in the pre-NTA period and certainly in the pre-land rights era in the Northern Territory under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth). In short, a claimant does not need to produce at a contested hearing a report by an anthropologist of a standard that would be favourably looked on for the granting of a doctor of philosophy degree at a leading university in Australia. Rather, the anthropology, as other expert evidence, must necessarily focus on what must be proved to satisfy s 233 connection requirements. Of course, the anthropology still needs to be of a high standard.

55 If claimants and respondents, usually in the first instance the government party, concentrate on what they know about the particular claim in front of them, having regard to their experience including in related or similar claims, they may decide that a particular approach to the identification of issues and their resolution is indicated. That is an approach that does not necessarily require any slavish application of guideline procedures or the production of a "connection report". That is not to say, however, that important ethnographic material will not need to be supplied in addition to what claimants say in that application.

56 By way of example, in one proceeding that I am currently case managing, following a preservation of evidence hearing at which the hearing judge received evidence and questions arose concerning Western Desert cultural bloc anthropology and related matters, I conducted a case management hearing at which counsel for the parties outlined, by reference to some of the ethnographic materials likely to be analysed by the expert anthropologists later, the nature of the anthropological issues that might possibly be at stake if the matter were to proceed to a contested hearing. I then ordered the exchange of reports between the parties and directed that the anthropologists to be engaged by the parties attend a subsequent case management hearing before me to discuss their preliminary assessments of the issues as they are then. It should be possible through this process to have the parties agree on what the real issues in the proceeding are. The outcome, in this case, may achieve an agreement about key issues more quickly than a conventional report preparation, exchange and discussion process that guidelines anticipate. The ultimate outcome of this process might be, if there is agreement about everything, a consent determination. Alternatively, there may be no agreement or only partial agreement about matters in issue and there may be a need for the matter to be listed for a contested hearing.

57 One way or the other, case management involving a judge along those lines, or in other contexts involving native title registrars along those lines, may enable the parties to identify the issues more quickly so that the resolution of the matter, whether by consensual agreement or otherwise, can be achieved more quickly and at less expense to the parties.

58 In that same process, questions may be more actively raised, by the parties or by the Court, as to whether or not this is a case in which a range of other, non-native title outcomes, might be considered, including as to compensation and the like.

59 It may be that in some cases the parties might engage in discussions as to a broader settlement along the lines of those achieved under the Settlement Act in Victoria, or as currently proposed in the single Noongar claim in Western Australia.

60 It may also be that if there are overlapping claimants, the real points in contest between those apparently competing claimants can be resolved, perhaps using techniques such as mediation, at an early stage rather than complicate the comprehensive resolution of a claim for months and years.

61 Additionally, the real interests of other respondent parties can be noted early on. Many, for example a body like Telstra, usually only require that their statutory interests be recognised in any determination, whether by consent or otherwise. They hardly need to participate in the court process thereafter, thereby avoiding unnecessary expense.

62 In relation to connection reports it should also be observed, as occurred in the relatively recent case of Oil Basins,[12] that claimants and the government party wish to maintain privilege in respect of connection reports and supporting materials and do not necessarily wish to share them with other parties during their early bilateral negotiations. That raises the question of dealings between claimants, government parties and other respondents which is referred to below.

63 In many cases, however, the best way forward, following an exchange of ethnographic materials, may be for the Court, subject to monitoring through case management, to leave it to the relevant parties – the government party and the claimants initially – to pursue their exchanges, reporting back to the Court as to progress.

64 Only if the dealings between those parties appear to have become protracted or intractable might the Court consider it appropriate to intervene.

65 There may also be other possibilities to the formal connection report process, including at an early date, arranging for the parties to receive information on country, in a sense along the lines of the taking of the preservation evidence in the matter just referred to.

66 In that sense, the abandonment of a formal connection report may be a stimulus to the adoption of innovative, more useful mechanisms for the parties to exchange information that will enable them in the more targeted way to come to a position on connection.

Should respondent parties, other than the government party, receive connection information from the outset?

67 This is another way of challenging current orthodoxy. Rather than under most existing processes having a connection report (or other connection material) initially being shared only between the claimants and the government party, with a statement of the "position" of the government party being advised later, should connection materials or a statement about connection be filed in the Court or otherwise provided, if necessary on a "without prejudice" basis, at the outset to all respondents?

68 This question has a particular resonance in Western Australia since the State indicated that it will no longer publish a "position paper" in relation to the acceptance of connection. That raises the question quite explicitly as to how the position on connection that is being taken, in principle, by claimants and the State, or other key respondents, should be communicated to all relevant parties.

69 As noted above, there will be a number of respondents – such as an entity like Telstra – whose only interest usually will be that their particular statutory interest be recorded and protected in any determination made under s 225 of the NTA. They will usually be agnostic about connection issues.

70 In other situations, however, as in the Oil Basins case, a particular party may wish to be more actively involved in determining its own position on connection and be less inclined to be influenced or guided by the State's position on connection.

71 If this is a growing feature of native title negotiations, then claimants in particular need to consider how they will engage with other respondents, apart from the State, who have indicated that they wish to be heard on connection.

72 The question of other respondents takes us back to the question of how s 61 applications should generally be case managed in the Court. In that regard, it is appropriate to mention that under the Federal Court's recently introduced National Court Framework (NCF) the native title practice area is one of the major practice areas of the Court. Before long a new practice note will be issued. It may be anticipated that the practice note will require an early case management hearing, a practice to be adopted in most other national practice areas. This reflects current practice. There will be a number of matters that need to be checked off at an early case management hearing. One of them could usefully be which respondents – as in the Telstra example suggested above – simply wish to have their interest protected when a determination is made, if it is made, and those who, provisionally at the outset, say they have a direct interest in the connection issue.

73 It will be interesting to hear from representatives of claimants as to how, under a regime like that which now seems to apply in Western Australia where a position paper will not be issued by the State, they propose dealing with those respondent parties, apart from the government party, who indicate an interest in connection in a timely way. Accordingly, as asked at the outset, should claimants file, even on a "without prejudice" basis, relevant connection materials in the Court so that they are, in effect, available to all parties?

74 At the very least, it would seem that it will be necessary for claimants to deal with a range of interested respondents on a one-by-one basis in that regard, along the lines they have been dealing with the government party to date.

75 A risk in expanding the current bilateral negotiations, from between claimants and the State to claimants and a range of other respondents, is that the whole connection process might blow out and become difficult to manage. The great value in the processes adopted to date under the formal guidelines has been that the government party does, at an appropriate point, indicate to all respondents the position they will take on connection. The fact that the government party takes as seriously as it does its connection inquiry functions and publishes a considered position in relation to connection has enabled most respondents to confidently rely on the position taken by the State. One suspects that, one way or the other, that practice will continue. The important question to resolve, if there is no position paper, is in what way or in what forum the position of the government party will be made transparent for all other parties to see.

76 One obvious answer to that question is that this will be done at case management hearings. The Court may invite the government party at an appropriate juncture formally to state its position.

Should current tenure be more accessible to inform claimant applications and negotiations?

77 As the indicative information about current negotiation and determination procedures set out in the attachment discloses, typically tenure analysis is only undertaken by a government party at the point at which the parties have agreed that a consent determination should be made, or the Court following a contested hearing has found that native title exists.

78 As the State of South Australia has indicated following the recent finding of the Court in Croft on behalf of the Barngarla Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia[13] proceeding that native title exists, the tenure analysis will now be conducted and is likely to take some time and possibly detract from the timeliness of tenure analysis in other proceedings in which the State is involved.

79 Similar observations about the burden that tenure analysis imposes on a government party, and its likely duration and expense, are not uncommon in other settings.

80 On the one hand, one can understand that if there is a real contest as to whether or not native title exists, a full blown tenure analysis at great length and expense may best await determination in a contested case, or soon after in principle agreement in a consent case.

81 On the other hand, experience seems to suggest, as the indicative information concerning the Northern Territory in the attachment suggests, that in many situations a current tenure analysis – which may be produced more quickly and at less expense – might for immediate purposes reasonably indicate the historic position.

82 The provision of a current tenure analysis may be considered, in a range of cases at least, of assistance to all parties. Claimants, for example, might reasonably proceed on an assumption, by reference to current tenure, that native title will have, prior to the operation of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth), wholly or partially extinguished native title. If land in respect of which native title has been wholly extinguished cannot be claimed, then the claimant application can be formulated with regard to that fact and negotiations may proceed on that basis. There will be no need to have a connection contest in respect of that land.

83 Similarly, if the current tenure analysis shows areas of land claimable under ss 47A or 47B of the NTA, then that might also enable the early identification of that land and the provision by claimants of relevant information to the government party as to why that land should be included in favourable a determination.

84 The primary question about tenure analysis is why, in principle, it ordinarily should be or must be hived off until after connection issues have been resolved. There may be good reasons for doing so in some cases, but surely those good reasons need to be articulated in each case?

85 Sometimes in response to questions as to why tenure analysis cannot be conducted sooner, a question of human resources is raised. The point is made that there are insufficient professionals to conduct the required work. A question must be asked, therefore, whether more human resources need to be applied to the task. Plainly all government parties and most other parties agree that native title claims under s 61 of the NTA should be resolved expeditiously and at the least possible cost to the parties. Those objectives fall squarely within the case management objectives of s 37M of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) which guide the conduct of native title proceedings as much as they do any other civil proceeding in the Court. I should add that it may be expected that the forthcoming practice note for native title will emphasise the overarching principle of civil litigation set out in s 37M of the FCA Act.

Should government parties and claimants' representatives endeavour to agree jurisdiction-wide extinguishment principles?

86 Presently, when the appropriate tenure analysis has been conducted, a process is engaged in – truly one involving rational analysis as a consequence of which beauty and inner peace of mind may well be found by the inquirer – as to what extinguishment has been effected by the grant of particular interests under statute or otherwise by the operation of legislation.

87 Extinguishment issues can be complex, and litigation has continued into recent times about the application of the principles laid down in Ward. The decision of the High Court in Brown[14] is perhaps a testament to that. However, at the same time, Brown confirms the principles established in Ward, particularly the inconsistency of rights test, and so it may be considered possible for the primary contesting parties, claimants and the government party to begin to agree what extinguishment principles apply within that State or Territory.

88 The question, of course, is whether the exercise is "worth the candle", worth the effort. On the one hand, rather than those relevant parties engaging in some protracted legal analysis as to whether or not extinguishment has occurred by reference to particular tenure, guidelines might indicatively answer the question. There could then be a further debate, in applying the guidelines, as to whether or not in the particular circumstances of a given case the guidelines produce the correct result.

89 Of course, the recent decision of the High Court in Queensland v Congoo[15] may, at least to some extent, be considered to complicate the extinguishment analysis. But at least if there were agreed guidelines, any grey areas could be identified.

90 The question really is, I think, whether the effort of endeavouring to agree guidelines about extinguishment is "worth the candle".

91 It may be that any guidelines created would become relatively redundant in a short period of time and the process is best left to direct negotiations between parties concerning their particular interests in each case.

Should claimants be required to demonstrate post-determination governance capacity in the course of negotiations in relation to a claim?

92 This question is asked because of the potential, whether after a determination has been made or before a determination has been made, for claimants or different groups of claimants to fall into disputation as to the management of the fruits of native title.

93 The decision of Rares J in Weribone,[16] a Queensland claim, is well-known. On the question of who the appropriate claimant should be, on a replacement of applicant application, his Honour found it appropriate to effectively freeze the funds the subject of an ILUA.

94 In a number of other cases, as noted, a feature of native title disputation is that there may be overlapping claimants and there may even be overlapping registered claimant groups, each with the ability to negotiate ILUAs and control the fruits of negotiation pending the hearing of the competing claims.

95 There is also a growing literature on the question of the governance of Aboriginal organisations and the need to ensure that prescribed bodies corporate (PBC) are adequately resourced and have the capacity to manage native title when a determination that native title exists has been made.

96 Rather than simply leave the resolution of governance and capacity issues to the time that they formally arise, should questions be asked in the earlier determination negotiation process, as to exactly how governance is to occur, how a PBC will be structured and managed and what voting and dispute resolution procedures will be put in place to deal with "royalty disputes" in the future.

97 If some of these questions concerning the constitution and operation of a PBC were to be asked at the outset, it is possible that a range of disputes currently involving overlapping claimants and funds management could be resolved in advance. Any tendency for "splinter groups" to form and go out on their own may potentially be resolved if all persons within a group with relevant native title interests understand early on how their rights and interests will be recognised and realised post-determination.

98 These questions of governance and capacity, of course, are not easily dealt with. But perhaps there is value in talking about them up-front in the claim negotiation procedures. The prospect of reducing or minimising trouble, turmoil and expense later is worth talking about.

Concluding observations

99 The judicial and registrar case management of native title applications, and the negotiation by parties of native title outcomes, is, in my view, at an interesting transitionary stage. Things are evolving.

100 The issues raised above are neither complete, in the sense that there are no doubt others that could be added to the list for discussion, but seek to identify some of the "challenging" issues facing native title management. I am not sure if any fall into the category of "dangerous" but some no doubt might produce strong differing views.

101 My intention in raising these points for discussion is to ensure that, as far as possible, the conduct of native title claims around Australia, across State and Territory boundaries, may evolve in ways that consistently advance the objects of the NTA.

102 In saying that, I do not wish to suggest that there should be a "one size fits all" approach to the issues raised. Indeed, I do not think that is the case at all. My concern is that to some extent, long-established current practices might unwittingly be adopting a "one size fits all" approach when greater flexibility to the management and negotiation of native title outcomes is appropriate.

103 In the management of native title cases in the Federal Court it may be said with some confidence that increasingly the Court will expect the parties to raise, at the earliest possible date, the range of potential issues and the possible means of agitating and resolving those issues in the circumstances of the particular case. Innovative solutions to old problems will be called for. So should consideration of the full range of non-native title outcomes that may enable the proper resolution of matters arising in native title. I welcome discussion on these topics and look forward to receiving feedback.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Indicative accounts of negotiating procedures adopted in various australian jurisdictions

Queensland

The connection process

104 The Queensland government has published a "Guide to compiling a connection report for native title claims in Queensland" (updated November 2013). This document is the basis for engagement between the State and the applicant in native title proceedings.

105 The State's position is clearly enunciated in the Guide. The introductory paragraphs explain the basis of the State's approach to the resolution of claims:

The State recognises that a native title claim group may demonstrate connection to traditional country in a variety of ways and that there is no simple formula for understanding relationships to country claimed under the NTA. The State also recognises the diverse and complex histories that Aboriginal people have experienced throughout Queensland since the establishment of British sovereignty.

Acknowledging these histories, the guide seeks to establish minimum parameters that are sufficiently open-ended so as not to exclude evidence that may help demonstrate the native title rights and interests claimed.

The purpose of this guide is to assist native title groups, their representatives and experts to prepare a connection report.

It is anticipated in most native title claims that a senior consultant anthropologist, engaged by the native title representative body (NTRB) or legal representative, will work with the native title claim group to undertake research into their claim and then prepare their connection report. Recognising the importance of professional anthropological advice in the compilation of an effective connection report, this guide has been produced primarily as a reference tool for consultant anthropologists engaged in the researching and writing of connection reports.

This guide does not offer any substantive discussion about the underlying legal issues that must necessarily inform the writing of a connection report. It is envisaged that input from a variety of professions may enhance the native title claim group's connection report. The author of a connection report may need to consider a number of key legal concepts that have been discussed in High Court decisions, particularly Yorta Yorta (2002) and Ben Ward (2002).[17]

(Emphasis added.)

106 The Guide suggests a format for compiling a report, the content of the report and advice about preparing material including repositories and records of relevant research.

The tenure process

107 The State has a broad policy that it will not commence tenure investigation until there is evidence provided by way of anthropological reports and witness statement that could inform substantive negotiations towards a consent determination.

108 Once the basic evidence is provided, the State commences current tenure investigations. The State, at first instance, relies on the Digital Cadastral Database (DCDB) that is maintained by the Department of Natural Resources and Mines (DNRM). The DCDB stores and processes information regularly supplied to it from survey plans, DNRM working maps and topographical information to produce data with respect to the spatial representation of parcel boundaries and their related textual descriptions and attributes. These attributes include a parcel (lot on plan) description, area and some current broad tenure categories such as freehold, lands lease, reserves, State Forests and National Parks. The DCDB does not store information with respect to mining tenements. Once a mapping officer has provided a claim boundary from the Form 1, the data produced by the DCDB can be extracted and compiled in an excel spreadsheet described as a claim browser.

109 In addition to the DCDB, there are currently four principal sources of information for tenure investigations undertaken by Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Land Services (ATSILS): the Automated Titles System (ATS), Mines Online, Smartmap Information Services (Smartmap) and non-computerised sources.

110 The State relies on an indicative tenure process to simplify tenure investigation in matters where the parties are working toward a consent determination. The indicative tenure process seeks to rationalise the evidence that must be obtained and led at a trial on extinguishment by facilitating agreement between parties on the basis of current tenure information.

111 The indicative tenure process is then provided for in any draft programming orders made by the Court by requiring the filing and service of a list of:

- current land and mining tenure information for parcels within the external boundary of the Claim Area (the current tenures);

- parcels where the current tenures meet the criteria of a previous exclusive possession act (PEPA) for the purpose of ss 238(1) to 238(3) of the NTA;

- together with illustrative maps depicting those tenures and an affidavit that details the source of the information (the indicative tenure documentation).

112 A critical difference between the indicative tenure process and the trial tenure investigation process is that the steps do not need to be undertaken for each parcel within the claim boundary. In particular, it is only necessary to obtain illustrative maps for those parcels where a current PEPA has been identified. This will result in substantial time saved as compared to the trial tenure investigation process. For example, where there are a large number of freehold parcels within a claim area, and assuming that each of those freehold parcels was granted on or before 23 December 1996, it would not be necessary to print the searches, which is a task that, at 5 minutes per parcel, would take a research officer approximately 10 weeks to complete).

113 Because of its finite resources, the State cannot meaningfully proceed to carry out tenure investigations on all native title determination applications simultaneously.

114 The State prioritises the allocation of its finite tenure investigation resources in resolving applications. The State does not prioritise the allocation of its tenure investigation resources to native title determination applications that are complicated by overlaps and/or which have no evidence of connection. This is because such a course would result in the reduction of tenure investigation resources for claims that have no overlaps and are supported by connection reports assessed by the State as being sufficient to enable it to enter into substantive negotiations towards a consent determination.

Western Australia

The connection process

115 The State first published guidelines for the provision of information in support of applications for determinations of native title" in October 2004, and now relies on the Guidelines for the Provision of Connection Material published in 2012. Upon receipt of connection materials from the applicants, the State will assess the materials and be informed by relevant expert and anthropological advice (either in-house or external or both), as well as legal advice from the State Solicitor's Office (SSO) and, if necessary, Counsel.

116 The Land, Approvals and Native Title Unit of the Department of Premier and Cabinet (Unit) is, amongst other things, responsible for conducting native title negotiations on behalf of the State. The Unit provides instructions to the SSO as solicitor on record before the Court. The Unit aims to resolve native title determination applications by agreement, where possible, consistent with the requirements of the Act and relevant case law.

117 The State, in most cases, provides an initial response to the connection materials, highlighting areas of concern or perceived deficiencies. The applicants then have an opportunity to answer the concerns or provide additional information or evidence. There can be quite lengthy exchanges between the State and the applicants. The nature and extent of materials provided varies from claim to claim, but can be very substantial. The connection process is closely supervised by the Court in case management and, in most instances, work plans are required which set out the timeframes for the provision of connection materials and responses from the State. In some cases the work plans have been formalised as orders of the Court.

118 Until the publication of the 2012 guidelines the State would issue a "position paper" setting out its view on connection. This position paper was also available to other respondents. However, in May 2014 the Court was advised that the State no longer publishes position papers in relation to acceptance of connection. It sees the issue of connection to be a matter for the applicant to satisfy other respondents about and not an issue for the State to deal with.

119 The State also no longer requires the acceptance of connection as a prerequisite for entry into substantive negotiations towards a consent determination, but forms its negotiation position based not only on the merits of the claim, but also the State's interests in the claim area, and the positions of other respondents. So, following receipt of the connection materials and the State's review of it, the State's approval process requires that, before it embarks on the process of substantive negotiations with the applicants, there be broad support from other respondents for that course.

120 If the State agrees to enter into negotiations towards a consent determination, the process in usually a bilateral, confidential and "without prejudice" negotiation between the State and the applicants without direct Court involvement in the discussions. The process is, however, monitored by the Court and any sticking points can either be intensively case-managed or, in some cases, mediated. Once there is broad agreement between the State and the applicant, the other parties are brought into the discussions, although their involvement in most cases is limited to issues of extinguishment.

The tenure process

121 The State's approach in relation to tenure was set out in letter from the Attorney General of Western Australia to the Court on 23 July 2013. In short, a tenure search involves the identification of all current and selected historical non-native title rights and interests (land, mining and petroleum) within the claim area. An analysis is then undertaken on the impact on each grant of the historical and current tenure on native title. Usually, not every item of historical tenure since the acquisition of British sovereignty is identified and analysed.

122 From the State's perspective, it is important to ascertain whether in respect of a particular area native title was extinguished or otherwise affected in circumstances which gave rise to a compensation liability on behalf of the State or not. Typically this involves inquiry as to whether the relevant extinguishment or other effect occurred before or after the commencement of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) on 31 October 1975. In general, in respect of any particular area, Landgate seeks to identify only the most recent wholly extinguishing act prior to 31 October 1975.

123 The State does not usually conduct investigation or analysis of public works (other than roads). It will generally rely on a general public works exclusion clause. The State takes a similar approach to pastoral improvements. In a consent determination context, the State does not usually investigate the extent to which reserves have been used for the reserve purpose in such a way that might result in complete extinguishment.

124 It is the State's view that although it will consider ways in which tenure analysis can be streamlined, there are few short cuts that can be made consistent with the administration of the law and the achievement of a proper determination. The State has said it will not be adopting an approach which has native title determined on current tenure alone.

Northern Territory

125 The procedures adopted in the Northern Territory are, in a number of ways, to be explained by reference to the "land rights" background that the Territory has, but few of the other States of Australia share.

126 Under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth), following an inquiry by a Land Commissioner, the Commonwealth government conveyed land to traditional owners through the mechanism of land councils. In this way effective Aboriginal control over much traditional land in the Northern Territory had been effected long before the decision in Mabo in 1992.

127 As a result, the push for recognition of native title under the NTA was more muted, although as the statistics above show, there has been much activity.

128 Whereas in other States single claims have typically been made in respect of the whole of the traditional country of a group of Aboriginal people, in the Territory there has, particularly in recent times, been specific claims made over particular pastoral leases. This obviously has been dictated by circumstances and has enabled the appropriate management of claims, having regard to limited respondent interests, as well as appropriate regard being paid to the ethnographical information that had been developed in the earlier land claims under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth).

The connection process

129 In recent times the "short report" has been utilised. It appears that the government party in the Territory has been satisfied that if appropriate information can be provided, albeit in a shorter report than might, for example, be required in other States under the guides, that should not be considered an impediment to the proper assessment of a claim and its potential resolution through a consent determination.

130 This is particular understandable in circumstances where, if a claim is being made over a pastoral lease in relation to which there is much ethnographic information already available as to which persons may hold native title rights and interests, this is an understandable pragmatic response by government which enables a claim to be resolved more quickly and at reduced expense it would otherwise be the case.

131 The use of short form reports, however, is still in its relative infancy and it is important to learn more about the advantages and potential disadvantages in relation to its use.

132 In the Northern Territory there is also the phenomenon of "town claims" and it is in this context that particular connection and tenure interests arise, as mentioned below.

133 In the Northern Territory once a position on connection has been reached between the claimants and the government party, those parties negotiate directly with all respondents. However, it should be noted that in the Territory there are usually few other respondents, unlike in other States where there are very often, very many.

The tenure process

134 In relation to town claims, in particular, the project addressed by National Native Title Tribunal President Raelene Webb QC in her paper, "Historic Tenure Certainty Project – A Tool For Sharing The Knowledge, Sharing The Future"[18], suggests that there are significant advantages potentially in undertaking a tenure analysis as a priority activity in native title negotiations, and at least to treat tenure an equally important first order consideration along with connection.

135 The town claims in the Northern Territory are a good example of this. If there can be agreement as to what extinguishment at material times has occurred, then some form of agreement as to native title, and non-native title matters, might be more easily approached and more quickly resolved.

136 The question might also be raised as to whether a tenure analysis prior to 1975 is of particular assistance. Depending on the circumstances, there may have been very little change in tenure both before 1975 and after 1975. It is understood that in some claims in the Northern Territory, the tenure position changed in only about 10% to 12% of parcels of land concerned.

South Australia

137 The following account of procedures typically utilised in South Australia is drawn from submissions made by the government party and the SANTS (South Australian Native Title Service) (for claimants) in recent times.

General progress

138 The State suggests experience has shown that concentrated effort on a small number of priority claims retains the parties' focus and momentum to produce lasting agreements and the State suggests that this approach continue.

139 The State also encourages the simultaneous resolution of connection and compensation claims for extinguishment if possible. It makes the point that if these issues can be resolved at the same time, a tenure analysis need only be completed once, ensuring certainty over the claim area and removing the probability of a subsequent claim for compensation.

140 This technique of dealing with connection, compensation and extinguishment at the one time plainly requires some close consideration.

The connection process

141 The State of South Australia, through the Crown Solicitor's office, native title section, has published "Consent Determinations in South Australia – A Guide to Preparing Native Title Reports". While published in 2004, it remains the current guide. It indicates that the State "is committed to resolving native title by negotiation rather than litigation wherever possible".

142 The guide was developed in consultation with the Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement Inc and explains that the State must be satisfied that a claim meets the legal requirements of the NTA before it can agree to a consent determination.

143 The particular criteria identified in the guide include demonstration of: the society of claimants; descent of native title holders at sovereignty; continued existence and vitality of traditional laws and customs; connection by traditional laws and customs; and rights and interests.

144 The guide identifies what the content of the report should be including expert opinion and forms of evidence.

145 So far as the assessment of reports are concerned, the guide indicates a nine-step assessment process.

146 Claimants provide the State with a native title report to support their position.

147 That report is informed by expert advice.

148 The State through the Crown Solicitor's office responds once it has advice from counsel and its expert.

149 In the event that the State and the claimants are unable to reach agreement that a consent determination should be made, there is the possibility, on the suggestion of the Court, that there be a further conference of experts to determine whether a "more unified view" can be reached in some cases.

150 In some proceedings where there is an intra-indigenous conflict, mediation between claimant groups is appropriately utilised.

151 The process of "negotiation" between the State and claimants may involve the provision to the State of counsel's advice and may also require the provision of more evidence by claimants to enable the State to form the view that a consent determination is possible.

152 In these circumstances, the Court case manages the dealings between the State and claimants, but does not usually actively intervene in those dealings.

The tenure process

153 An Historic Tenure Project developed by the State and SANTS with the National Native Title Tribunal has been put to the Commonwealth for grant funding under the Indigenous Advancement Strategy.

154 This project offers the prospect of tenure analysis being conducted earlier on in a native title proceeding than has been the usual experience.

155 The usual situation is, as in the case of the Barngarla (where the Court has found recently that native title exists) that tenure analysis follows determination. The State has indicated it has a very large task ahead of it to extract all relevant historical tenure information, analyse it and agree on its effects with the solicitors for the Barngarla.

156 The State has made the point that, as a result, resources will have to be diverted from completing tenure work and other priority claims and it is unlikely that any significant tenure work will be able to be progressed in other claims for some little time to come.

157 The State also makes the point that, with the majority of remaining priority claims in South Australia covering more settled areas, tenure is likely to be considerably more complex to extract and analyse, often involving tens of thousands of parcels and likely to take considerably longer to complete.

158 These observations emphasise the importance of considering the timing and methods by which tenure analysis is undertaken and completed.

New South Wales

The connection process

159 The New South Wales government does not have a published policy in relation to assessing connection evidence in native title determination applications. This has made it difficult for the Court to clearly understand the processes that the State uses when assessing connection evidence.

160 In October 2012, however, the Court made orders in the Barkandji Traditional Owners native title matter (NSD6084/1998) that required the State to file a document identifying its processes and procedures and the steps it generally takes in order to assess and determine its position on the issue of connection. The State provided correspondence to the Court in compliance with those orders.

161 The correspondence indicated that the State aims to settle native title determination applications by consent rather than by litigation. The State, in assessing connection evidence, seeks evidence that is consistent with the requirements of the NTA. Further, the State is informed by the relevant case law, particularly in regard to the way in which the Court has made consent determination orders pursuant to s 87 of the NTA.

162 The State's threshold for accepting connection evidence is that of a "reasonably arguable case" as described by North J in Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v State of Victoria (No 5).[19] Further, in order for the State to be satisfied, the applicant's connection evidence must be "reasonably cogent", detailed, clear, and open to assessment. The evidence must broadly cover all of the areas claimed. The formal assessment process is conducted by the State's legal practitioners, including Counsel. However, the legal assessment is informed by the opinions and comments of in-house historians and anthropologists.

163 The State may provide preliminary comments to the applicant if it appears on the face of the evidence that it may be lacking, so as to allow the applicant to address the deficiencies prior to the completion of formal assessment. This approach, it is stated, often encourages a 'back and forth' between the parties where supplementary connection material is provided in a piece meal way.

164 It is worth noting that this process, at least in the Barkandji matter (admittedly a very large claim), led to the State considering a very considerable volume of material over a seven year period (2006-2013), including:

- 42 affidavits

- 7 expert reports

- 1 genealogy

- 2 volumes of source material (containing 19 sources)

- 5 other documents provided under s 94L directions in National Native Title Tribunal mediation (including a compilation of 20 affidavits; Statement of Facts, Issues and Contentions; locality map; photos; table setting out how the affidavit evidence addresses the claimed rights and interests).

165 The Court has more recently taken the approach of closely monitoring the connection processes in NSW, by early referrals to case management by a Registrar of the Court, and by making standard orders requiring the applicant to provide its evidence within a specified timeframe, and for the State to provide its assessment within a similar timeframe. Orders are also made requiring the State to provide, where it forms a view that the evidence is insufficient, a comprehensive outline of the reasons why the evidence was insufficient so that issues can be identified and addressed in an efficient way.

166 More recently, the Court has required, in matters where the connection process remains ongoing, the applicant and State to file a report setting out the connection issues remaining to be resolved as between them and the processes and timeframes proposed to resolve those issues.

167 While there has been no change in stated policy in NSW, the monitored approach has, in at least one instance, seen significantly shortened connection processes. For example, the connection process in the Western Bundjalung matter (NSD2300/211) took a total of 15 months for the State to accept the applicant's evidence as sufficient to establish connection. That is to be compared to the Barkandji matter where the connection process took a total of seven years.

The tenure process

168 In an affidavit filed by the State on 6 February 2014 in the Barkandji matter, the State identified the processes it undergoes when analysing tenure in a native title determination application. The State's tenure process is two-staged: the collection and collation of raw current and historical tenure data; and legal assessment and analysis of that data as to the effect of certain tenures on native title.

169 The Status Branch, Department of Trade and Investment, completes the first stage of the tenure process by preparing full historical status reports, including identifying and collating all historical supporting evidence. The second stage of the process is conducted by the State's lawyers, including counsel. The status reports include information including, but not limited to, parish maps, Crown plans and tenure cards. There may be several thousand or more reports prepared for a single native title determination application. For example, in the Bandjalang People #2 matter (NSD6107/1998), over 9,000 status reports were prepared taking a total of 17 months to complete. This period did not include timeframes for completing the legal analysis by the State nor subsequent negotiations with the applicant in relation to the effect of any tenure.

170 The State affidavit further estimated timeframes for completing full historical tenure searching for NSW native title matters in the future on the basis that approximately 72 status reports can be completed per calendar month if six officers were working full time on the task. Based on the State's current practice for tenure searching, the Western Bundjalung matter would take approximately 16 months to complete; the Gomeroi People matter (NSD2308/2011) 19 years to complete; and the Ngemba/Ngiyampaa matter (NSD415/2012) eight years to complete (none of these proposed timeframes were concurrent).

171 At an interlocutory hearing on 14 February 2014, in which the State affidavit was filed in support of an extension of time for the provision of a tenure analysis by the State, Jagot J expressed concerns with the way in which parties were conducting the tenure processes in NSW native title matters. Her Honour observed:

it's staring us in the face that what's happening right now is unsustainable; unsustainable for the State, unsustainable for the Court, unsustainable for the applicant, unsustainable for every party … That means the system does have to change …What has been happening in the past fails to recognise the nature of court proceedings - civil proceedings in the court.

It fails to have any sense of proportionality between the rights that are ultimately going to be obtained and what impact they could possibly have on anybody and the resources that are being used to determine tenure issues … the disconnect is profound between those two things[.]

172 Her Honour stated that it was not an efficient tenure process to complete comprehensive historical searching of every single parcel within a native title claim area. Rather, parties should take a "rational, proportional, sensible" approach to tenure processes through prioritisation of parcels of importance and categorisation of tenure by way of completing analysis of a random sample of those categories.

173 Following these comments by her Honour, the State has been exploring different ways of streamlining its tenure processes. These have included enlisting the assistance of the National Native Title Tribunal to create an electronic tool to assist in assembling tenure information into electronic mapping. It is clear that the timeframes anticipated by the State are being considerably shortened, however there have not been any public pronouncements/documents that refer to a new approach.

174 The Court has been actively managing tenure processes in NSW through intensive case management and/or mediation of tenure negotiations between the applicant and State, and by making orders for the provision and analysis of tenure material within specific timeframes. Where required, the Court has also made orders for the filing of a document by any party who has an outstanding tenure issue after a particular date and the setting down for hearing of any tenure disputes so as to ensure that tenure processes are not open-ended. This regime has been effective in assisting the parties to reach agreement with final compromises being reached in the Yaegl matter after the notices of dispute were filed but before the hearing of those disputes.

Victoria

175 In 2010, the Victorian government developed an alternative system to native title for recognising the rights of traditional owners. The Settlement Act allows the government and traditional owners to make agreements that recognise traditional owners' connection to the land and provide them with certain rights on Crown land. The Settlement Act was developed in consultation with traditional owners through the Victorian Traditional Owner Land Justice Group (Land Justice Group), whom had advocated, on behalf of traditional owners, for an alternative approach to resolving native title claims in Victoria. Further, the Land Justice Group assisted the Victorian government to develop policies that underpin the legislation. Native title matters in Victoria are now often settled under the Settlement Act by way of a non-native title agreement (such as an ILUA), for example the four Dja Dja Wurrung matters (VID6006/1998, VID6001/1999, VID6003/1999 and VID6001/2000) were settled under the Settlement Act in 2014.

176 The Victorian government has prepared guidelines as to the threshold requirements to be met in order for traditional wwners to commence settlement negotiations with the government. There are two stages to the threshold process. The first stage requires Traditional Owners to prepare a statement that sets out the basis of the claim group, area descriptions for a proposed agreement, and the group's traditional and cultural association to the proposed agreement area. The second stage requires the traditional owners to be ready and prepared to commence negotiations for a settlement agreement, including the creation of a Traditional Owner Corporation, appointment of a negotiating team and development of a plan that sets out the group's aspirations. It is interesting to note that the Victorian process "front loads" the requirement to demonstrate that the traditional owner group is able to negotiate and the establishment of corporation that will manage the benefits.